Inhalt

Seite 1

IntroductionSeite 2

Data and Summary StatisticsSeite 3

ResultsSeite 4

Endnoten Auf einer Seite lesenResults

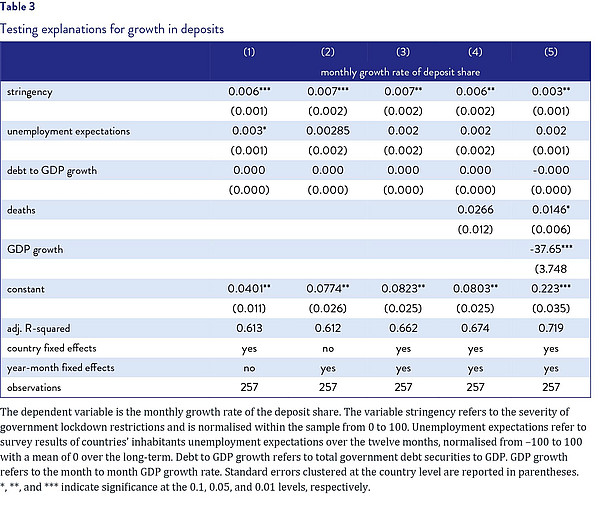

Table 3 presents our results with different levels of fixed effects for the following regression model:

ΔDepositsi,t = β0 + β1Stringencyi,t + β2ΔGovDebti,t + β3E[U]i,t + ωt + δi + ϵi,t

where ΔDepositsi,t refers refers to the monthly growth rate of in the household deposit share in country i at time t, Stringencyi,t refers to the monthly average of the government mobility restrictions index from OxCGRT in country i at time t, ΔGovDebti,t refers to the level of government debt, E[U]i,t refers to employment expectations of households at time t in country i, ωt capture monthly time fixed effects, δi captures country fixed effects and ϵi,t refers to the error term, which we cluster at the country-level.

The coefficient on the index of government lockdown stringency is relatively consistent across various fixed effects specification, ranging from approximately 0.006 to 0.007 in our preferred specifications. Because the stringency index is normalised from 0 to 100, this implies that, on average, an increase from its minimum to its maximum results in the monthly deposit share growth rate being 0.6 percentage points higher – equivalent to two standard deviations. To put this magnitude in more concrete terms, had Germany gone from no restrictions to that of the level observed in Italy in March 2020, this would be equivalent to Germany’s deposits increasing by roughly 14.3 billion euros – or approximately 348 euros per household every month.

One concern may be that the coefficient on lockdown severity is upward biased by the severity of COVID-19. Households may fear that shopping, eating out, or travelling exposes them to an increased risk of infection, inducing them to avoid consumption opportunities. One would also expect that COVID-19 severity should be positively correlated with lockdowns as governments respond to the increased threat of the virus. To address this concern, in Column 4, we control for COVID-19 severity by including total monthly COVID-19 deaths per one million inhabitants sourced from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in the regression model. We find a coefficient on monthly deaths that is not quite statistically significant at the 10% level. Importantly, the coefficient on lockdown stringency is only marginally reduced in this specification relative to in columns 1 through 3.

Finally, in column 5, we include GDP growth in the model to ensure the relationship in the deposit share is not simply driven by the effect of lockdown stringency on GDP, which in turn impacts consumer confidence and thereby consumption. These results should be interpreted with caution as GDP growth should be subject to reverse causality with respect to deposits, as a decline in demand should also result in lower GDP growth. Here the magnitude of the impact of the lockdown is reduced from approximately 0.007 to 0.004. However, even if the lockdown drives deposits in part via its impact on GDP growth, this still would point to the lockdown as the root source driving the rise in the deposit share. Moreover, GDP growth may simply be capturing some of the variation in the severity of the lockdown. Hence, while this provides evidence that there is indeed a direct effect of the lockdown on deposits, it is unclear how to interpret the decline in the magnitude of the coefficient on lockdowns.

We find that the relationship between unemployment expectations and deposits is weak or inexistent. Only without time fixed do we observe a relationship that is statistically significant at the 10% level.

We also find no statistically significant relationship between government debt and changes in the deposit share in a panel setting. The cross-sectional relationship between the two perhaps reflects the fact that places more severely hit by the virus also happen to be places with stricter lockdown regimes and a greater need for a government fiscal response. In other tests (not shown), we find that the relationship between government debt and deposits vanishes once we control for time fixed effects, country fixed effects, lockdown regimes, or any combination of the three. This is reassuring from a policymaking perspective, because it suggests that there is currently no trade-off between aggregate demand and government spending.

Discussion

We construct a monthly panel of eurozone members and assess the ability of precautionary motivations, mobility restrictions, and government debt to explain the recent increase in household savings. We find strong evidence for the importance of lockdowns in explaining savings, weak evidence of precautionary motivations, and no evidence that this rise is explained by increasing government debt.

We interpret our results as being optimistic for the COVID-19 recovery. Unemployment expectations can take years to recover, as was the case in the Great Recession. Government debt levels can take even longer to return to pre-recession levels. However, lockdowns can quickly cease once a critical share of the population is vaccinated. The fact that households will, on average, exit the crisis with more wealth than they had going into the crisis should bode well for the recovery of consumer confidence and for financial stability more generally.

Some have raised concerns that post-COVID-19 spending could be too much of a good thing and that economies could be faced with inflation rates in the two-digits in the coming years.7 We view these concerns as overstated, even if inflation in excess of the ECB’s target is a real possibility. According the ECB, professional forecasters anticipate a five-year average inflation rate of just 1.7%8 and market expectations implied by five-year swap rates are at just 1%.9 Should European governments be faced with inflation following the easing of the lockdown, they can quickly scale back emergency fiscal rescue spending, and this is without mentioning the tools at the ECB’s disposal. Finally, for struggling firms with little pricing power, a temporary bout of inflation slightly above the ECB’s target of 2% may even be a welcome development.

Moreover, it is still uncertain to what extent households will spend their newly accumulated wealth as soon as mobility-restrictions are removed. Many may simply return to their pre-COVID-19 consumption habits, using the wealth for retirement or to eventually purchase a first home, all of which would bode well for financial stability in the long run.

In any case, at present, deflation seems to be the more immediate threat. The moving twelve-month average inflation rate for the euro area in October was a measly 0.5% and is even negative in five euro area countries.10 Deflation could further incentivise households to refrain from spending and with lockdowns in place, there is little room for fiscal and monetary policy to induce more demand if people do not have opportunities to spend.

Our results do not find any evidence that there is currently a tradeoff between government spending and aggregate demand. Indeed, while we do not find that precautionary savings play a large role in the increase in the deposit share, this would perhaps be different had governments played a more subdued role in mitigating the economic burden of the COVID-19 crisis.

Finally, our data does not incorporate the more recent lockdowns implemented in November and December across the eurozone in response to the “second wave” of COVID-19 cases. In general, there is little reason to think that the recent lockdown had a different effect from the earlier one, given that consumption possibilities were similarly restricted as before with stores closed, mobility restrictions increased, and restaurants limited to takeout, etc.