Significant Cooling of the Economy – Political Risks High: Joint Economic Forecast Spring 2019

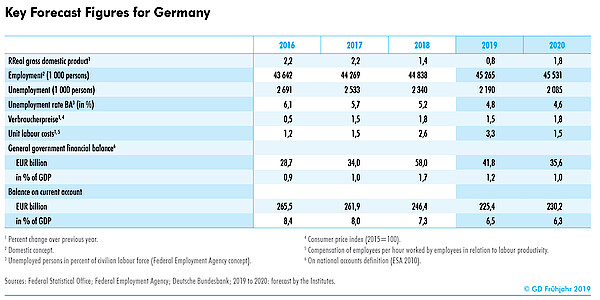

Die Konjunktur in Deutschland hat sich seit Mitte des Jahres 2018 merklich abgekühlt. Der langjährige Aufschwung ist damit offenbar zu einem Ende gekommen. Die schwächere Dynamik wurde sowohl vom internationalen Umfeld als auch von branchenspezifischen Ereignissen ausgelöst. Die weltwirtschaftlichen Rahmenbedingungen haben sich – auch aufgrund politischer Risiken – eingetrübt, und das Verarbeitende Gewerbe hat mit Produktionshemmnissen zu kämpfen. Die deutsche Wirtschaft durchläuft nunmehr eine Abkühlungsphase, in der die gesamtwirtschaftliche Überauslastung zurückgeht. Die Institute erwarten für das Jahr 2019 nur noch ein Wirtschaftswachstum von 0,8% und damit mehr als einen Prozentpunkt weniger als noch im Herbst 2018. Die Gefahr einer ausgeprägten Rezession mit negativen Veränderungsraten des Bruttoinlandsprodukts über mehrere Quartale halten die Institute jedoch bislang für gering, jedenfalls solange sich die politischen Risiken nicht weiter zuspitzen. Für das Jahr 2020 bestätigen die Institute ihre Prognose aus dem vergangenen Herbst: Das Bruttoinlandsprodukt dürfte im Jahr 2020 um 1,8% zunehmen.

04. April 2019

Contents

Page 1

Global economyPage 2

German economyPage 3

Economic policy All on one page

The economic situation varies considerably from region to region: in the US, the upswing merely slowed down, whereas in the euro area, it came to a standstill in the second half of 2018, mainly due to the pronounced weakness of German and Italian industry. Signs of an economic slowdown in China came in the early part of last year, but only the country’s very weak imports in the final quarter of 2018 suggest a downturn there.

To some extent, the cooling of the global economy in the course of 2018 is better understood as a normalisation after the exceptionally strong upswing in 2017. However, it is also a consequence of major economic policy risks. It is still not clear how the trade conflict pitting the US against China and the European Union (EU) will play out. The second uncertainty in Europe is the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. It is unclear whether this will be regulated by an agreement or unregulated, or if and for how long it will be postponed.

The international economy also faced a headwind in the form of US monetary policy. In 2018, the US Federal Reserve raised its key interest rate by a total of one percentage point to a range of 2.25–2.5%, and as a result financing conditions in many emerging markets deteriorated significantly at times. Other dampening one-off effects in the third quarter of 2018 included natural disasters in Japan and weak vehicle sales in many places, partly due to difficulties in converting to a new exhaust gas testing system in the EU and elsewhere.

It is not only in the automotive sector, but also in manufacturing in general that the economy has cooled off sharply. This may be partly because duties or risks of tariff increases usually affect trade in goods, but not in services. At any rate, the mood in manufacturing companies in almost all countries has deteriorated much more dramatically than among service providers, and world industrial production has lost considerably more momentum than the economy as a whole. Not least because the service sector remains intact, employment in most advanced economies has expanded until recently, albeit at a slower pace, and wage growth has tended to accelerate, with unemployment often very low. However, except for oil-price-related fluctuations, consumer price inflation remains generally low (as in the euro area and in particular Japan) or moderate (as in the US).

Against this backdrop, monetary policy in many places has reacted to the economic slowdown and suspended or loosened the tightening course previously adopted. The US Federal Reserve announced its change of course in January 2019, the European Central Bank (ECB) in March. However, as early as the end of 2018, players in financial markets were no longer expecting near-term hikes in key interest rates in the US, and capital market yields have tended to decline since then. A return to more favourable financing conditions is of particular benefit to emerging markets, which are dependent on inflows of foreign capital.

Fiscal policy varies from region to region. In the US, it is less expansionary, with the stimuli from the tax reform adopted at the end of 2017 and from spending programmes expiring in the forecast period. An increase in Japanese VAT in the autumn of 2019 will have a restrictive effect. In contrast, fiscal policy in the euro area will change this year from being more or less neutral to being slightly expansionary, mainly due to measures taken in Germany and Italy. Finally, the Chinese government has decided to introduce substantial tax cuts for consumers and companies in order to stabilise its economy.

Economic policy will therefore generate opposing stimuli in the forecast period: on the one hand, monetary and fiscal policy will support the international economic situation; on the other, high levels of uncertainty about the progress of the trade disputes and the UK’s withdrawal from the EU continue to weigh on the global economy. Leading indicators, for example, do not paint a clear picture of the international economy in the first half of 2019: the mood in industry has fallen until recently, as have incoming orders. In addition, US production in the first quarter is likely to have been significantly dampened by the government shutdown in January and the severe cold in February. However, other indicators also point to the possibility that the economic cycle has bottomed out: share prices and prices for many industrial commodities rose again at the beginning of the year, and risk premiums – measured by the yield spread between otherwise comparable bonds issued by issuers with different levels of risk – fell. In addition, consumer confidence in advanced economies in general remains high. The upswing in the US will probably continue for some time despite temporary dampening effects and the economic policy measures in China are likely to gradually take effect. Taken together, these facts also point to a somewhat stronger expansion of production in the further course of this year. Furthermore, it is to be expected that the economies of some emerging countries will pick up again in the current year after slowing significantly in 2018.

In 2020, US and euro area production will expand close to their potential, while the trend towards somewhat lower growth in China will continue. All in all, it is to be expected that overall economic production in the countries considered here will increase at a rate of 2.7% (weighted by exchange rate) in 2019 and 2020, which is significantly slower than in 2018. Compared with the Joint Economic Forecast for autumn 2018, this represents a downward revision of 0.3 and 0.2 percentage points, respectively. The slowdown is even more pronounced from a German perspective (world production weighted by the shares of German exports). World trade in 2019 is likely to be only 1.6% higher than in 2018, but will pick up noticeably over the course of the year.