The Nasty Gap

30 years after unification: Why East Germany is still 20% poorer than the West

Dossier

In a nutshell

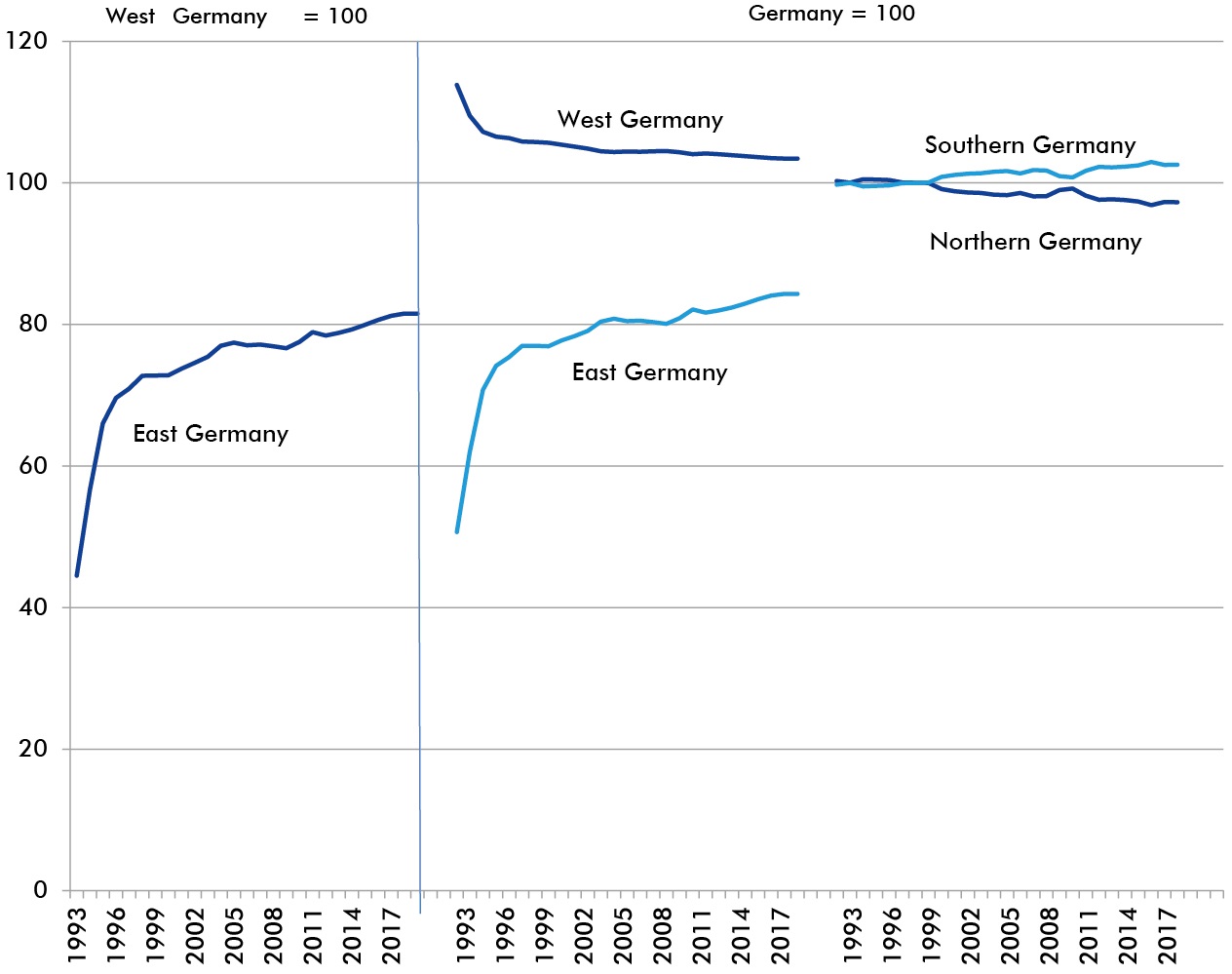

The East German economic convergence process is hardly progressing. The economic performance of East Germany stagnates between 75% and 80% of West Germany's level, depending on the statistical figure used. The productivity gap between East German companies and equivalent groups in the west remains even if firms of the same size of workforce and the same industry are compared.

The fundamental reason for the stagnation of the convergence process lies in the lack of productivity of eastern German companies. They were unable to grow under their own steam. Political decisions at the beginning of the transformation and the brain drain to West Germany are having an effect here. In addition, there is the permanent subsidization of unproductive structures and a lack of entrepreneurship, which can be explained by the lack of capital reserves and the experience of the disruptive change of the political and economic system. Crucial to overcoming the productivity gap are investments in education and research, digital infrastructure and a culture of internationality.

Our experts

President

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-700 Request per E-Mail

Vice President Department Head

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-800 Request per E-MailAll experts, press releases, publications and events on "East Germany"

Regardless of whether the gap is measured by economic output per capita, disposable income or labour productivity: East Germany is still 20% to 25% poorer than West Germany. But the regional differences are much smaller in the east than in the west. Even the poorest West German states, however, are still wealthier per capita than all East German states (with the exception of Berlin). Nevertheless, compared with the initial situation in eastern Germany at the time of German unification, the development represents a huge improvement.

According to economic convergence theory, the gap should have closed after twenty years at the latest. The political border and trade barriers had disappeared; institutions and language were the same in East and West Germany. Capital and labour could move freely. The East German states should have attracted investment because of initially low wages and operating costs, and skilled workers should have moved to the well-paying jobs in the West until wages and returns on capital in East and West Germany converged.

The Historical Handicap: Deindustrialisation and Planned Economy

Historically, many of today's wealthy regions in southern Germany were significantly poorer than the urban centers of eastern Germany such as Saxony and Berlin. At the end of World War II, all German regions started from scratch, but East German industry was less devastated because it was partly beyond the reach of Allied bombers. However, brutal deindustrialisation then ensued, with large parts of industry and infrastructure literally dismantled and transported to the Soviet Union. At the same time, East Germany was cut off from international trade flows and deprived of its main markets and sources of capital in West Germany.

Thus, at its founding in 1949, the GDR started out with a per capita productivity one-third lower than that of West Germany. Nevertheless, a remarkable reconstruction succeeded. At the beginning of the 1970s, the GDR was still on a par with the southern EU countries. In the 15 years before the fall of the Wall, however, the stagnation of the socialist bloc also affected the GDR. The economic situation shortly before the end in 1989 was much worse than many studies, including Western studies, had estimated.

There were two positive exceptions: GDR agriculture was more efficient than the small-scale West German agriculture due to its organization in cooperatives with very large land areas per farm. And the level of education was on a par with that in West Germany, even somewhat higher in the technical and engineering professions.

In the GDR planned economy, the allocation of capital, natural resources and labour was for four decades the result of political determination rather than the logic of the market. In addition, the GDR had to adopt the specialization assigned to it in the socialist economic network. As a result, urban regions in particular were disproportionately oriented toward heavy industry, while in West Germany they were at the forefront of the transformation to a service economy.

After Unification: Initial Boom, then Stagnation

In the first few years after reunification, the convergence theory seemed to prove true: The GDR economy caught up quickly. Ten years after the fall of the Wall, per capita income had skyrocketed from 35% of the West's level to 65%. One key factor in this success was the first wave of privatisation under the first democratic GDR government, which freed small companies in particular from the shackles of the planned economy. On the other hand, the ailing infrastructure was brought up to a competitive level with an enormous investment of state funds.

At the end of the 1990s, this initial catch-up momentum came to a halt. Since then, the East German economy has mostly grown even more slowly than the West German economy, and income equalization continued only in tiny steps over the next twenty years. The fundamental reason for this abrupt halt in the convergence process is the lack of productivity of East German companies. They were unable to grow under their own steam.

The Revaluation of the Currency

One reason for this was the establishment of the 1:1 exchange rate between the GDR mark and the Deutschmark. Politically, there was probably no alternative to this decision, since otherwise high inflation rates and a mass exodus of the East German population to the west of the country would have been likely. Economically, it was tantamount to a fourfold revaluation of the currency. Many East German products and services lost their price competitiveness. Households and companies groaned under the suddenly multiplied burden of their debts in East German currency.

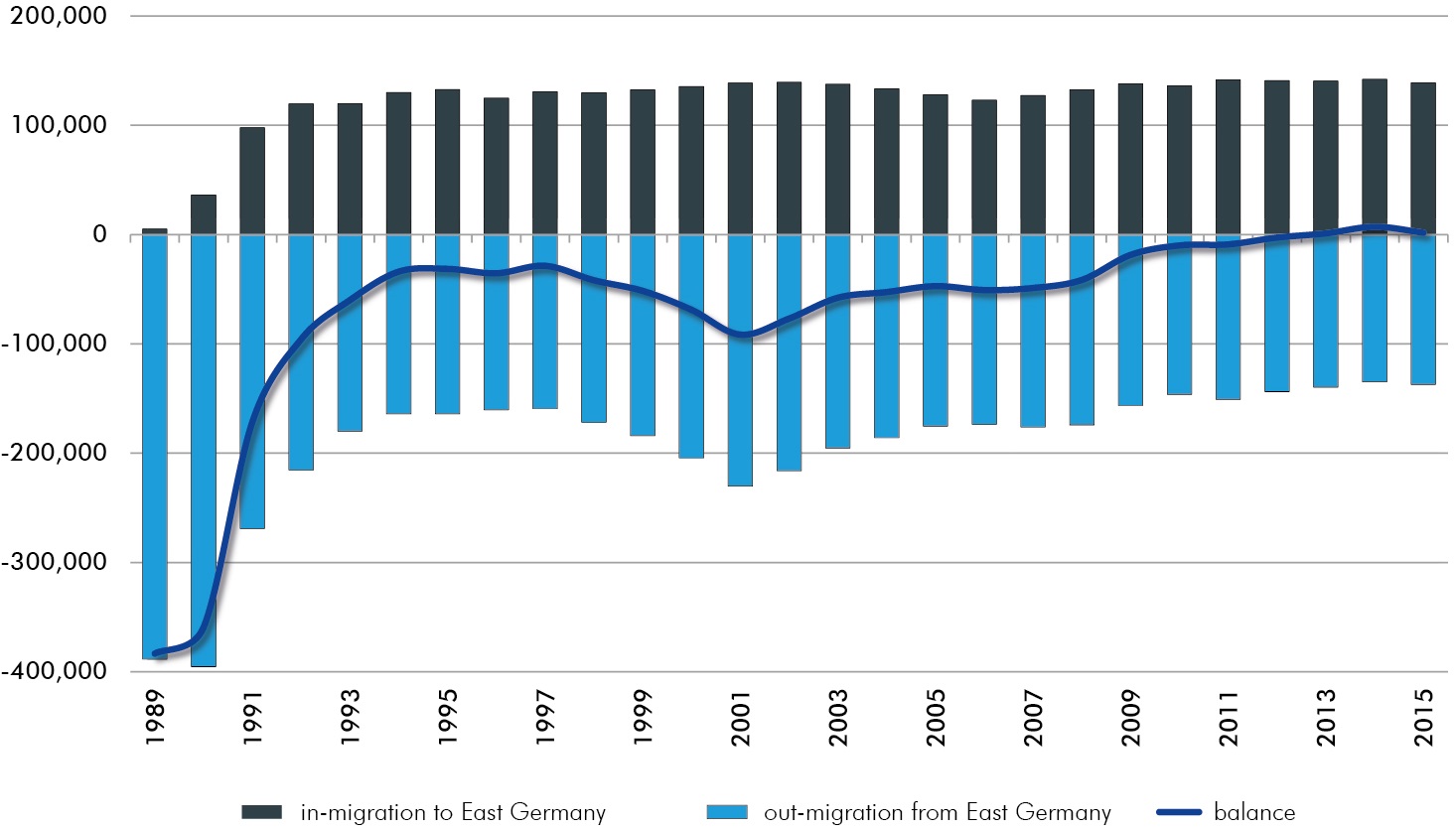

The Brain Drain

Despite the 1:1 conversion of their salaries and savings, the incentives remained high, especially for the many well-educated engineers and technicians in the GDR to migrate to West Germany. They could often earn three times as much there. Between 1989 and 2013, a net 1.9 million mostly well-educated people emigrated. By comparison, a total of about nine million people of working age lived in the GDR. To be sure, this emigration prevented unemployment in eastern Germany from skyrocketing even higher. On the other hand, the East German labour market was devalued: It was mainly the less well-educated and older people who were left behind. This is the second reason for the persistent productivity gap in eastern Germany.

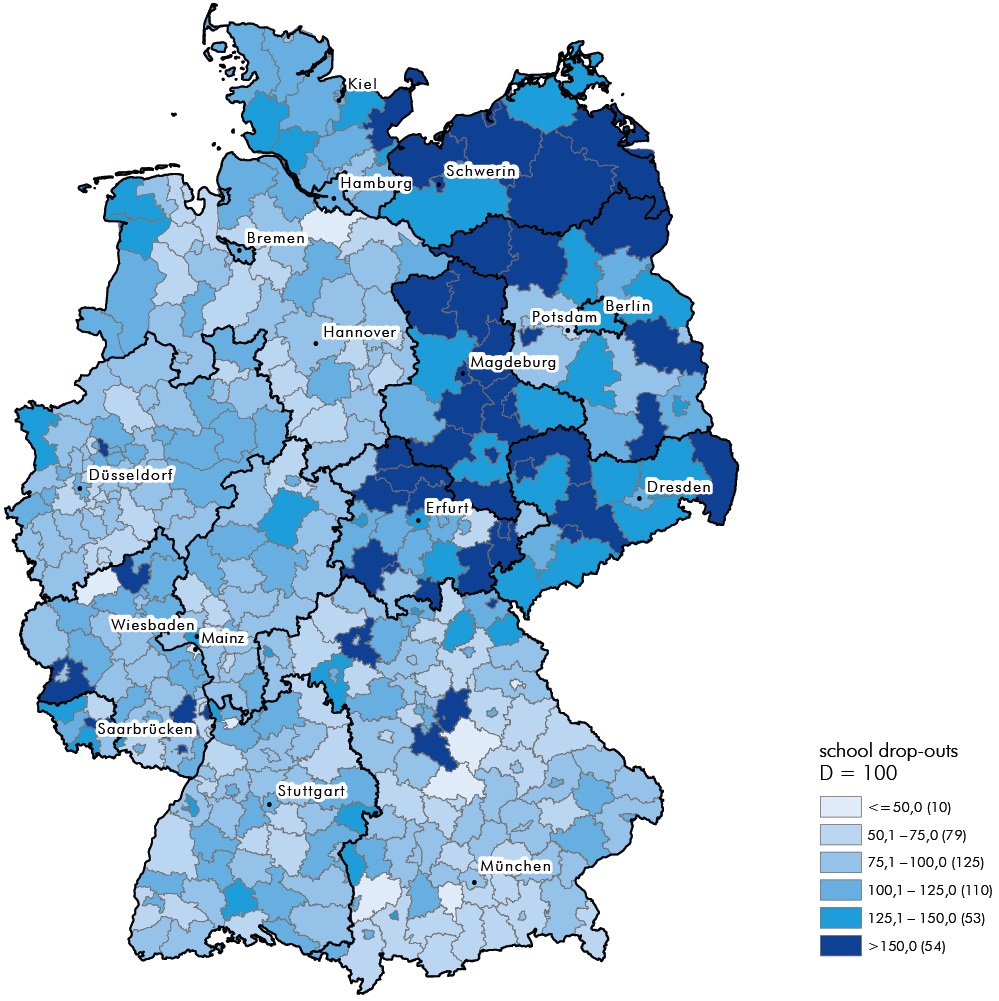

By contrast, the West German economy, which in the early 2000s was the "sick man of Europe," benefited enormously from immigration from the East German states. It rejuvenated the working-age population and improved its level of education. This contributed significantly to the recovery of the German economy in the following decade. It more than compensated for the fiscal outflow of funds to support and rebuild the East German economy and infrastructure in the 1990s. To this day, the East suffers from this brain drain, the consequences of which will be perpetuated into the next generations: Today, the proportion of well-educated people in eastern Germany is significantly lower than in the west, while the school dropout rate is above average.

The Treuhand Privatization

The third reason for the insufficient and non-self-sustaining productivity of East German companies is rooted in the second wave of privatization, which primarily affected the large industrial conglomerates. The enormous task of taking over the 8,500 (after the breakup of the largest conglomerates, as many as 12,000) state-owned industrial enterprises with four million employees and finding private owners for them was entrusted to the Treuhandanstalt, which was still founded by the Modrow government. When it was dissolved in 1995, the Treuhandanstalt had sold most of the plants; however, 3,700 plants had to be closed. The Treuhand privatization was associated with enormous job losses and the social problems that went with them. For fifteen years, there was a persistently very high unemployment rate in eastern Germany, which only began to decline again in 2005 (but has been falling steadily since then).

Could there have been another way of privatization, with less harsh side effects? Even at the beginning of the process, two schools of thought confronted each other. One would have preferred to privatize more cautiously and gradually, restructuring the companies first under state supervision and making them fit for the market. The other, liberal school advocated immediate privatization, leaving the decision to restructure or close inefficient capacities to the market. In practice, the second position prevailed. In retrospect, however, it is undeniable that, with exceptions such as Carl Zeiss and Jenoptik, the approach of rapid privatization has often not worked well. High unemployment in the 1990s and the loss of productive capacity in the East may have been too high a price to pay, especially in terms of social dislocation. The question of whether gradual privatization would have achieved better results is the subject of scientific evaluation of the Treuhand files, which have only recently been published.

Labour Market Gap Closed – Productivity Gap Persists

Beginning with the economic recovery after the recession at the turn of the millennium, unemployment in eastern Germany has steadily declined, from 18% to currently around 6%. Migration to the West, infrastructure modernization and the transformation to a service society have contributed significantly to this. Today, in view of the rapidly aging population, the shortage of skilled workers has replaced unemployment as the central challenge of the labour market in the eastern German states.

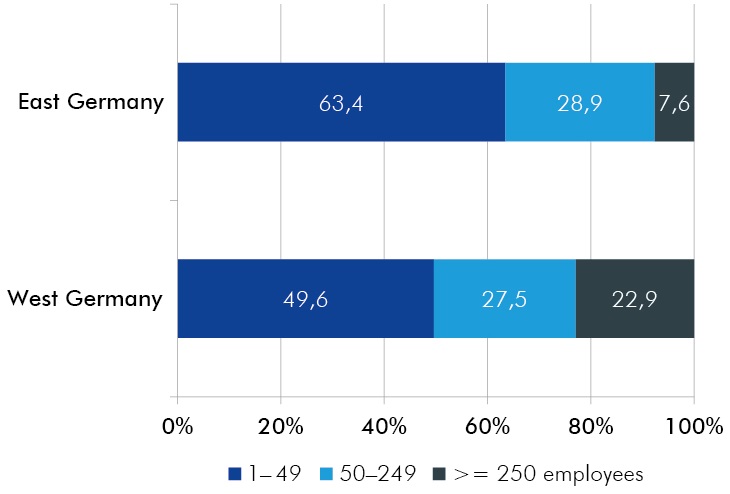

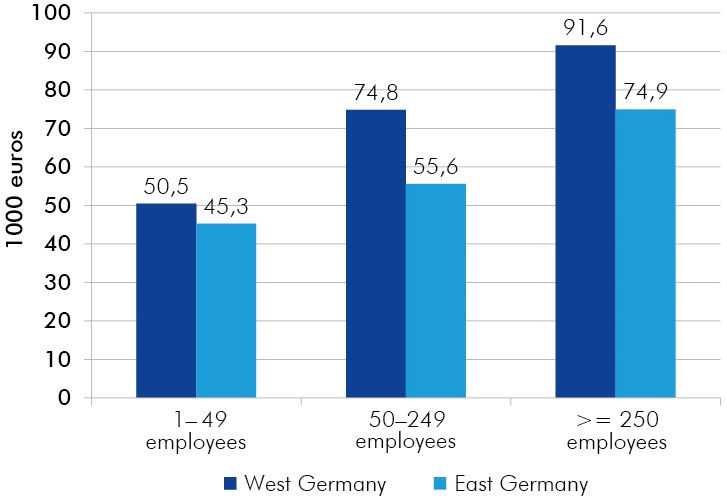

While the east-west gap in the labour market has largely closed, the productivity gap persists. East German firms produce less output with the same input than West German firms – even when East-West differences in size and industry structure are taken into account, i.e. East German firms are compared only with West German firms that are the same size and operate in the same industry. What are the reasons for this? Three factors that were at the beginning of the transformation process and continue to have an impact today have already been described: Revaluation shock, brain drain and Treuhand privatization. Another reason is the ongoing state subsidization of unproductive companies.

Subsidies Keep Unproductive Plants Alive

The case of Buna-Werke is exemplary for the practice of this subsidization. VEB Chemische Werke Buna produced chemical products from lignite and, with 30,000 employees, was one of the largest industrial combines in the GDR. The plant produced with obsolete technical equipment and under immense environmental pollution. The Treuhandanstalt was unable to find a private buyer for a long time. Most of the well-trained workforce emigrated. Only after 2000 was it possible to sell the company, which in the meantime had shrunk to 3,000 employees, to the U.S. group Dow Chemical, with three billion euros in state subsidies flowing to the buyer. In arithmetical terms, the preservation of one job cost the state one million euros.

All in all, the state subsidized the preservation of eastern Germany's industrial base to the tune of about 50 billion euros over the past three decades, thus artificially keeping inefficient, no longer competitive structures alive. This was undoubtedly done under the impression of the impending social consequences of major plant closures, but also because many decision-makers had in mind the image of the West German, industry-driven economic miracle, which they wanted to copy in East Germany. In doing so, they failed to recognize that modern economies had long been on the way to becoming service economies. In the 1990s, for example, far more industrial jobs were lost in western Germany than in the eastern part of the country.

Today, given the shortage of skilled workers, there is no longer any sociopolitical justification for state aid to unproductive companies. If the well-qualified employees allocate to the best companies in the future, the east-west productivity gap will narrow.

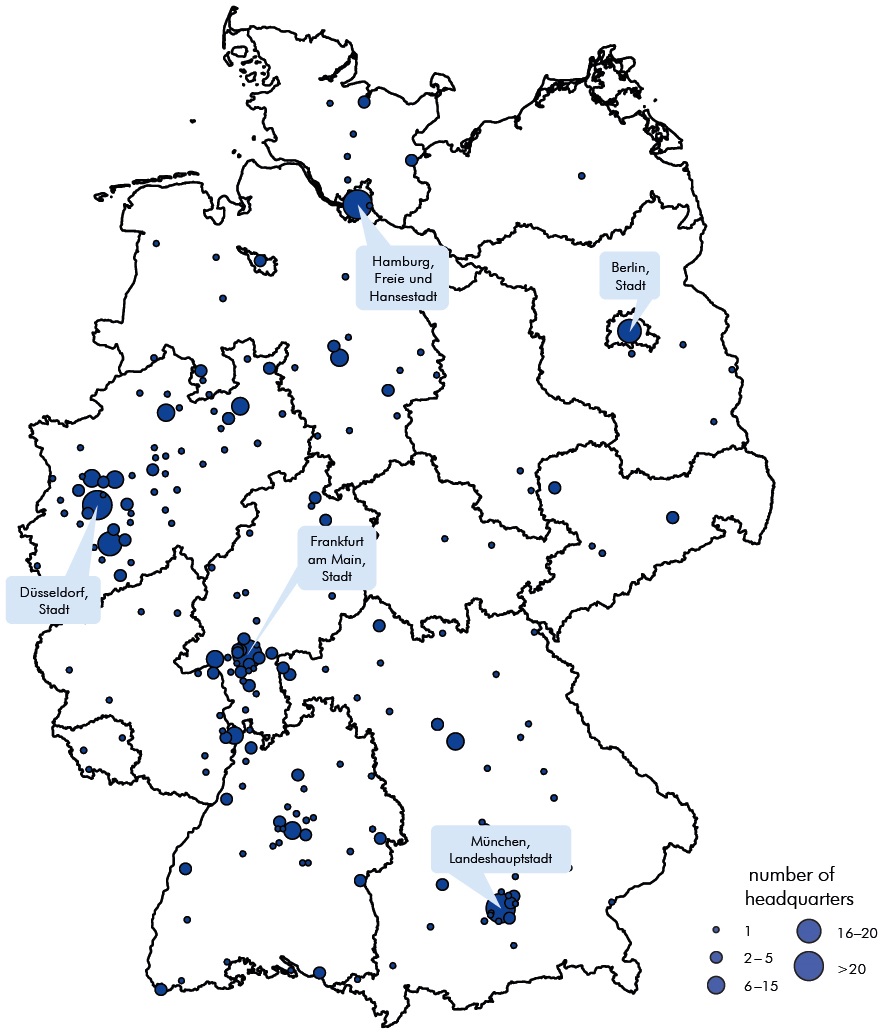

Aging Capitalism – No Unicorns in Sight

Finally, there is another reason for the East's productivity lag: "aging" German capitalism. Only 2% of the 500 largest German companies (by capitalization) were founded before 1990, compared to 20% in the US. There is a lack of young, fast-growing companies that challenge the incumbent firms, especially so-called unicorns, i.e. startups with a capitalization of more than one billion euros.

Nevertheless, Germany has so far managed to remain above-average in terms of innovation within its traditional focus areas of automotive engineering, chemicals and mechanical engineering. However, the corporate headquarters where the greatest value added is created are located almost exclusively in the west of the country. This part of the productivity gap can only be closed by establishing new companies in eastern Germany and growing them to appropriate sizes. However, the conditions for this are rather unfavourable in Germany in general and for eastern German startups in particular. The remarkable startup scene in Berlin is still too young and too small to fundamentally change this.

Education and Digital Infrastructure

In the future, state funds should flow primarily into the eastern German education and training system. Those who enjoy excellent qualification opportunities in the region do not have to migrate. Good daycare centers for children, good schools and universities are attractive to highly qualified and skilled workers from abroad and their families. University graduates are potential company founders, and they often start up near their home university. But basic education must also be strengthened and the high number of school dropouts compared to the West reduced.

To enable a high-tech economy, infrastructure investments should in future flow primarily into the expansion of fast digital networks.

Immigration and Welcome Culture

The population of eastern Germany is aging faster than that of western Germany. Although there are some fast-growing cities with young populations, such as Leipzig, Dresden and Berlin, in many small eastern German towns and rural areas, on the other hand, one hardly encounters people under 50. However, there are also positive signs: for a decade now, migration to the West has stopped, and the birth rate, which collapsed after reunification, has also returned to the West German level.

What is missing is stable net immigration from abroad. After the financial and euro crises of 2008/2009, many well-qualified people immigrated to Germany, especially from southern Europe; however, their destination was almost always western Germany, where they could build on existing networks of compatriots. The resentment toward immigrants, which is more pronounced in eastern Germany than in the west, already poses a massive economic problem. Well-qualified people who are in demand elsewhere already perceive the political rhetoric of populist parties and groups, conveyed by the media, as hostile and do not consider East Germany as a new home where they are welcome.

Risk Avoidance as a Legacy of Transformation

Market economy means risk. It is possible that the fundamental cause of the persistent economic East-West gap lies in a reluctance to take risks that is more pronounced in East Germany. This attitude is understandable from the experience of transformation: Those who, like the East Germans, experienced how from one day to the next the familiar system of material and social values, certainties and relationships completely collapsed and was replaced by another in which one had to start from scratch often tended to act more cautiously in the future and avoid risks. Few people have been able to personally transform this epochal rupture into positive energy and see the opportunity it presents to reinvent themselves.

In addition, unlike West Germans, people in East Germany did not have the opportunity to accumulate capital in the form of monetary assets, real estate and social networks over decades of a prosperous economy and over several generations. Such a reserve for unforeseen events provides security and makes it easier to take risks for promising prospects.

Disproportionate risk aversion, distrust of innovation and the future in general are strong underlying currents that are also passed on to the next generation, which did not live through the GDR era itself. Entrepreneurship is much less common in the East, even among those born after 1980. The comfort zone is preferred to innovation and the possibility of personal growth.

Perhaps this is the heaviest legacy of the Wall.

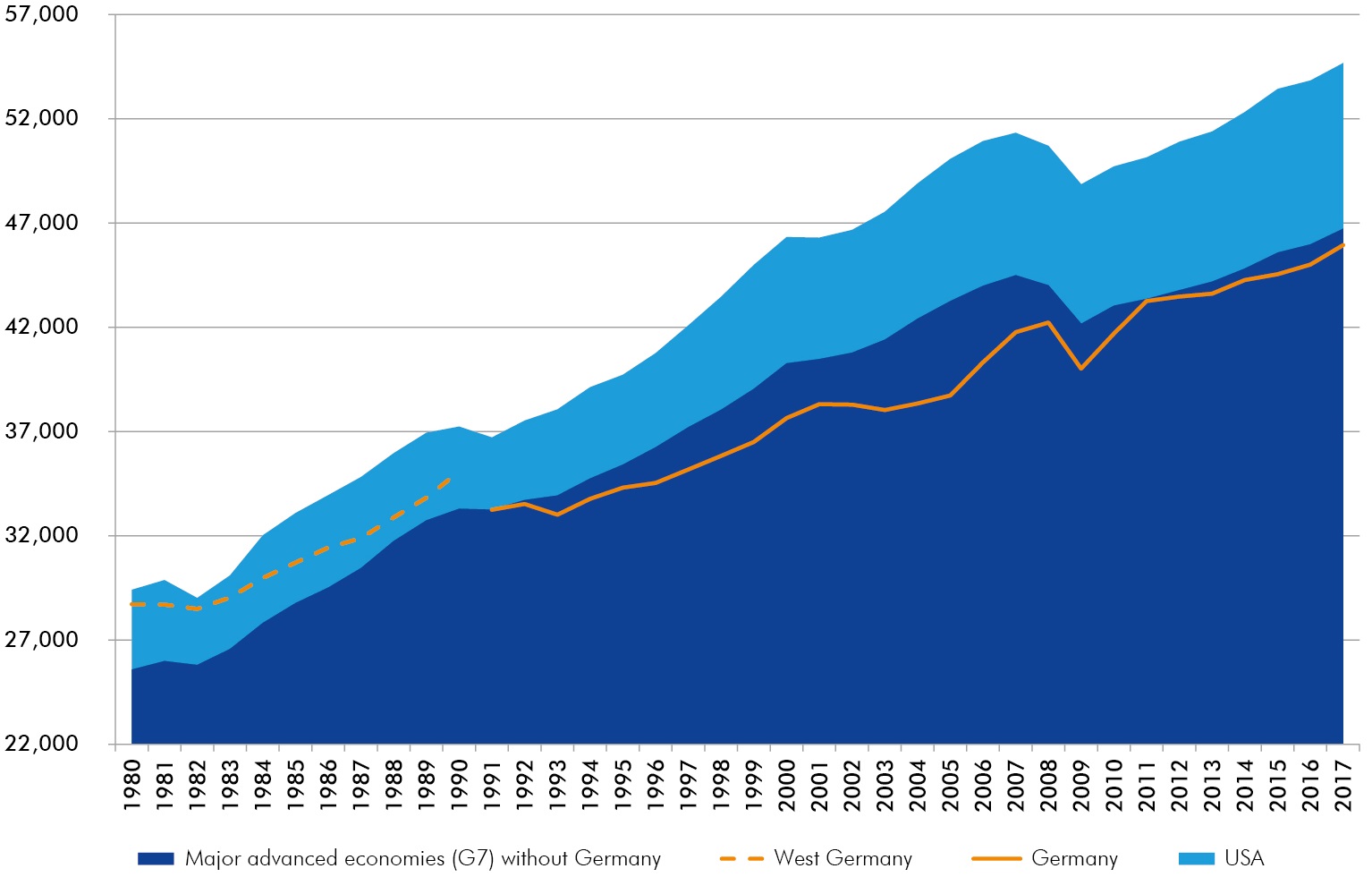

The German economy has overcome a period of weakness following reunification

Gross domestic product per capita, purchasing power parity, 2011, international dollar

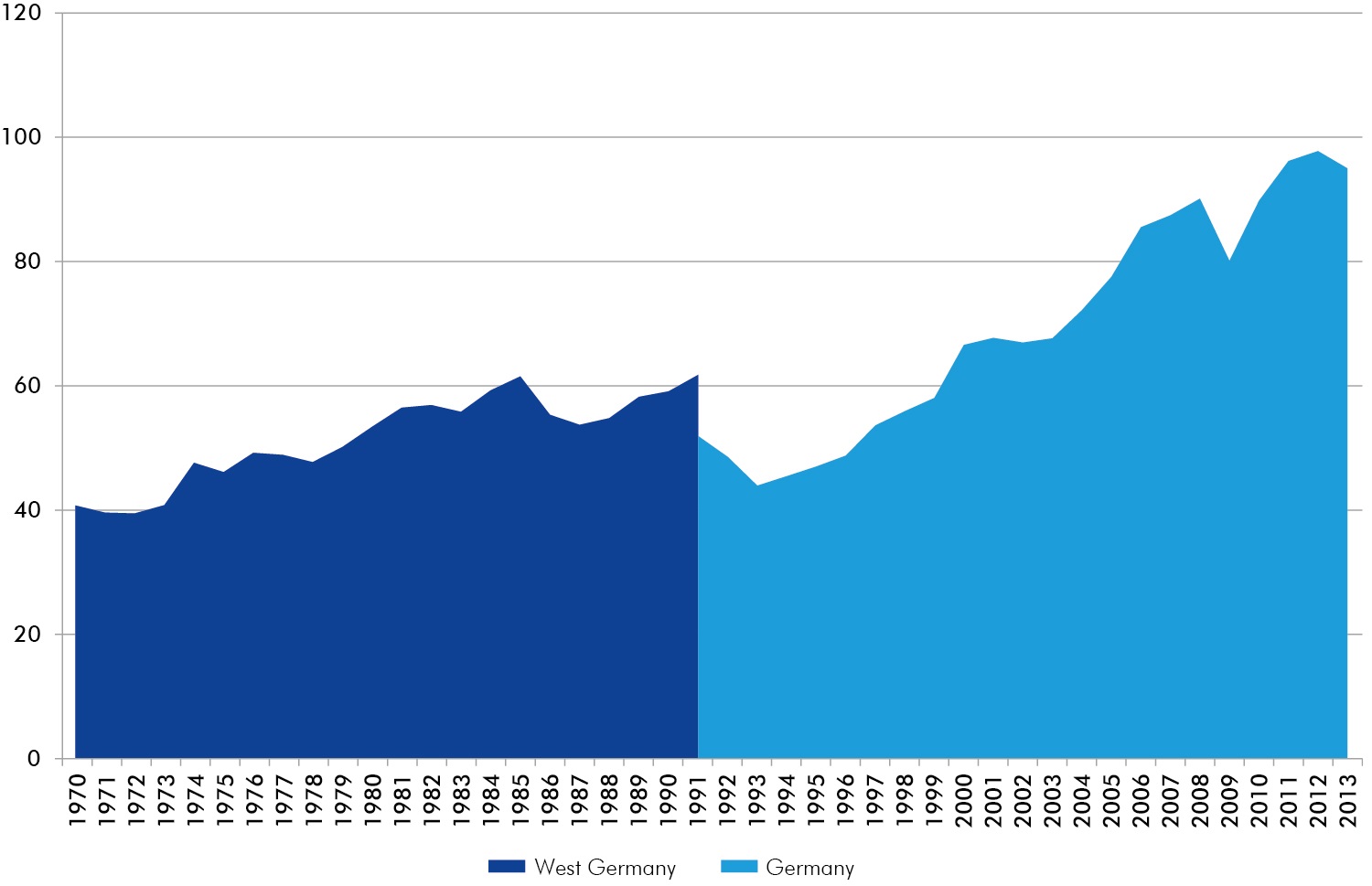

Degree of openness of the German economy

Gross domestic product per capita, purchasing power parity, 2011, international dollar

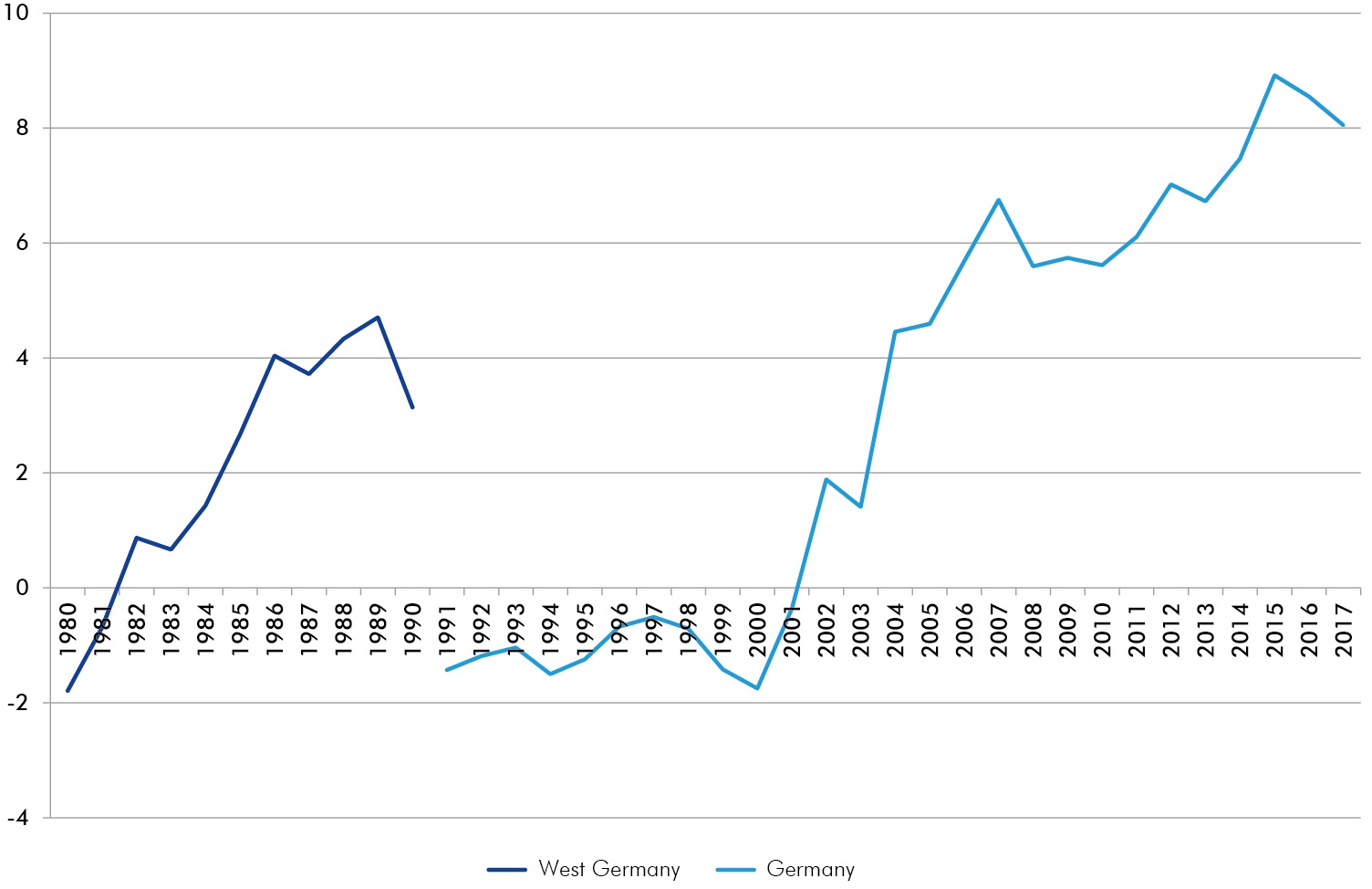

Current account balance

Relative to gross domestic product, in %

Productivity differences in Germany between west and east

Gross domestic product in current prices per employee

East-west differences in productivity in companies of all sizes

East-west differences in productivity in companies of all sizes

Hardly any corporate HQs in East Germany

Headquarters of the TOP 500 companies in Germany 2016 ranked by DIE WELT

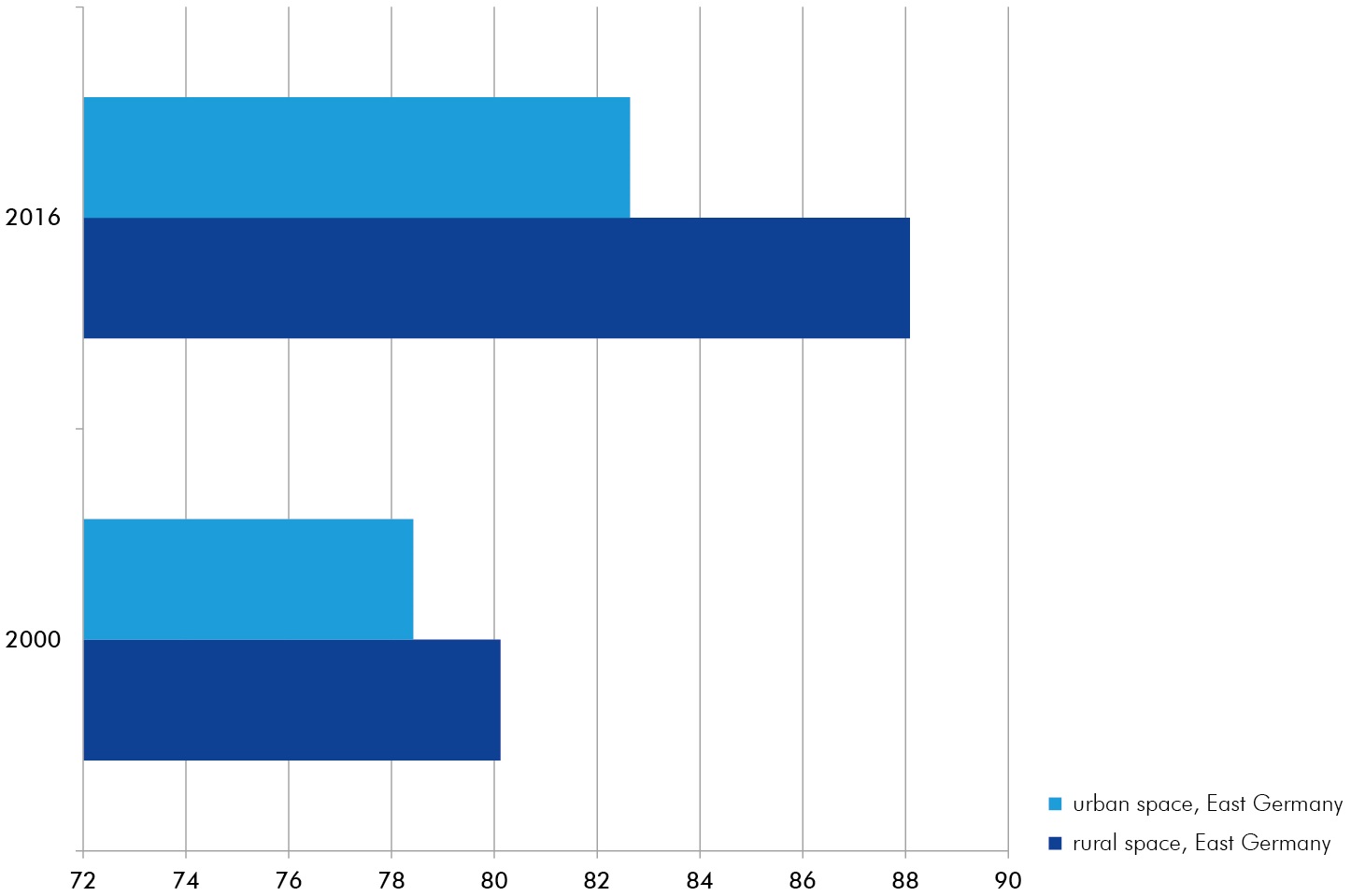

East-west productivity differences are smaller in rural areas than in cities

Gross domestic product per employee in urban and rural spaces in East Germany including Berlin, spatial category in West Germany = 100

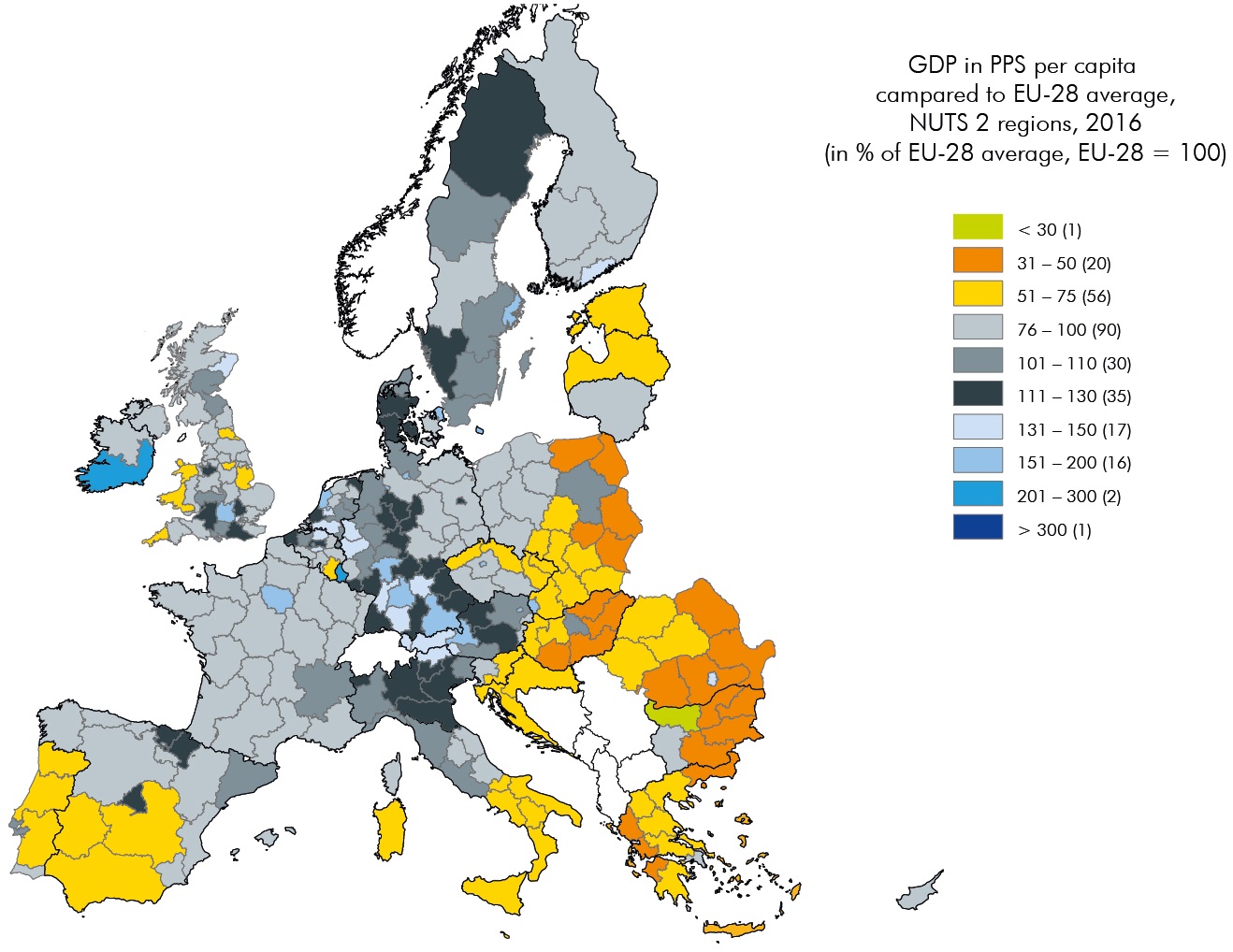

Economic output per resident in German regions compared to European regions

Gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power parities (PPS) per capita 2016

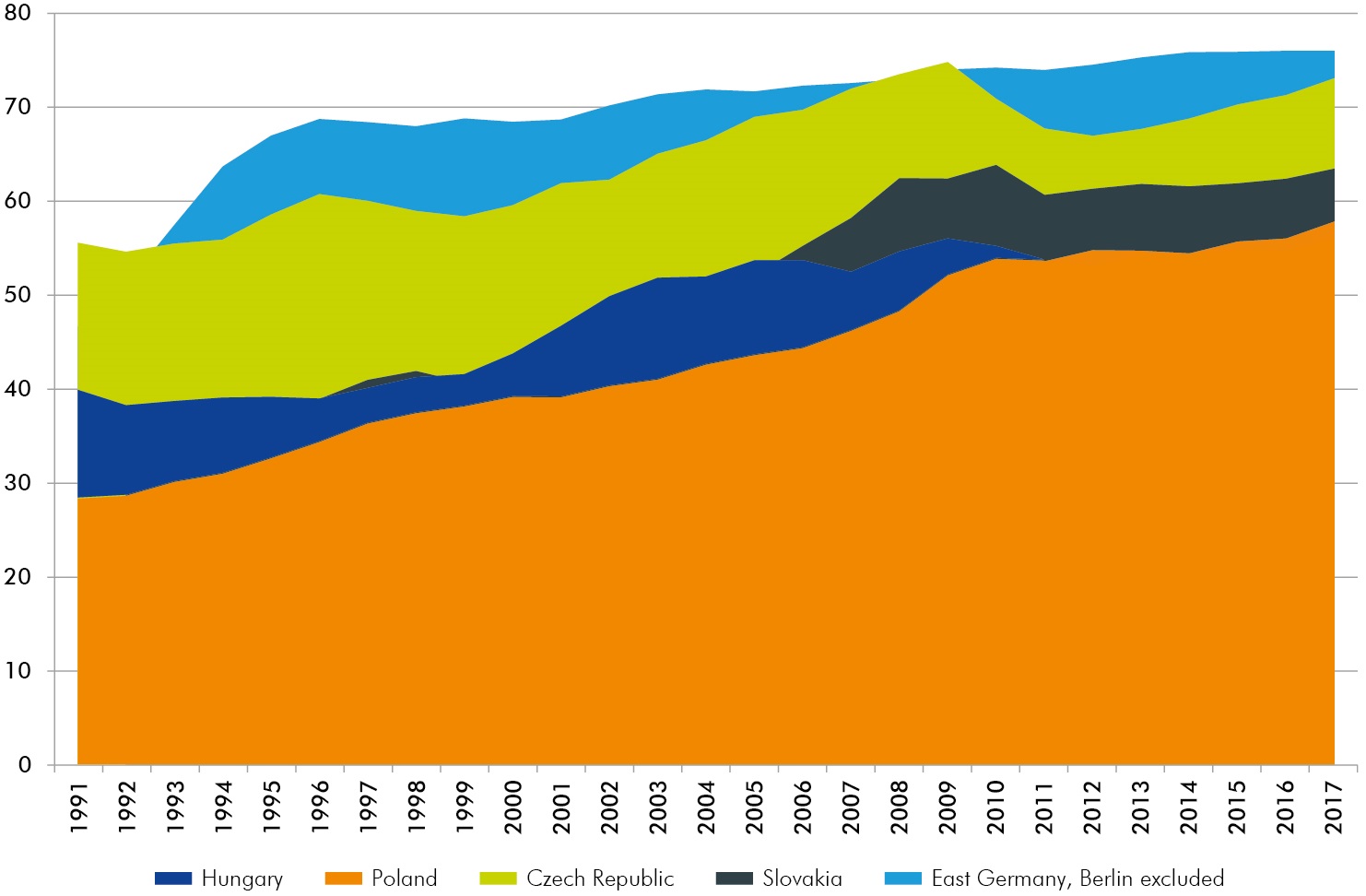

Economic output per capita in East Germany higher than in the Visegrád countries

Gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power parities relative to Germany, in %

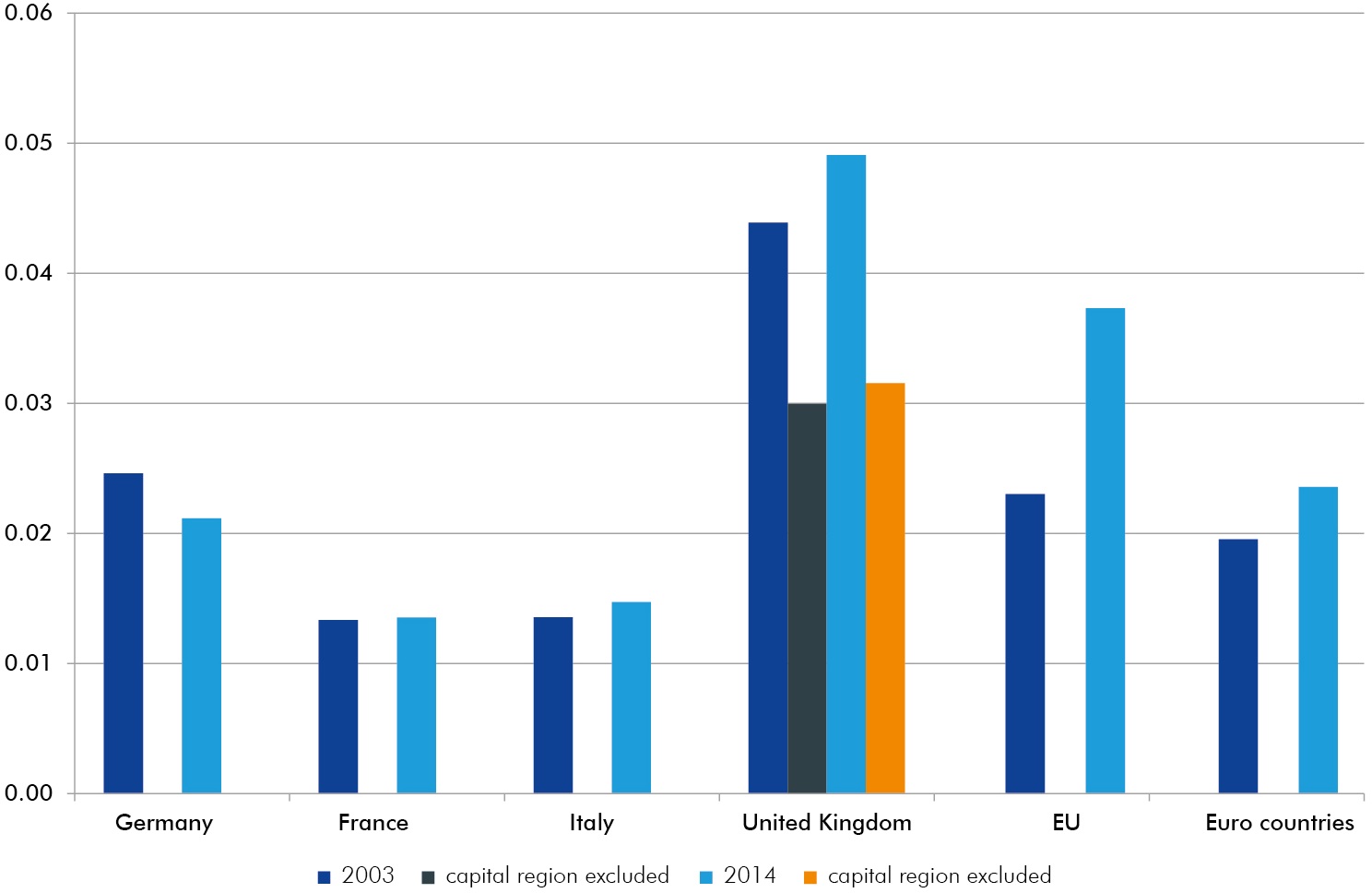

Germany‘s regional income disparity has lessened compared to other European regions

Variance of gross domestic product, lograrithmised, purchasing power parities

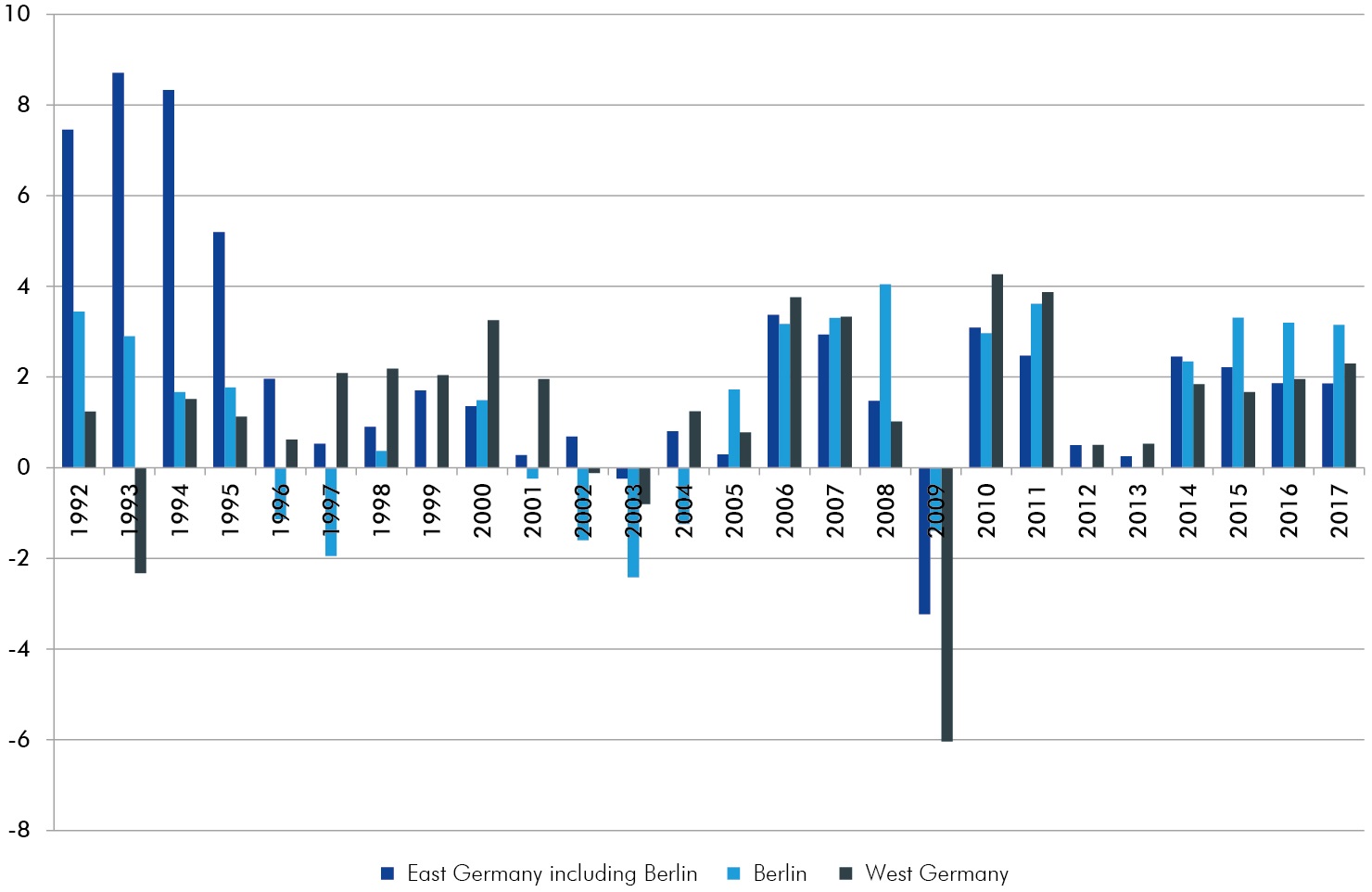

East Germany has only recorded a more favourable development of economic output than West Germany in 11 out of 26 years

Yearly rate of change of gross domestic product, price-adjusted, chain-linked, in %

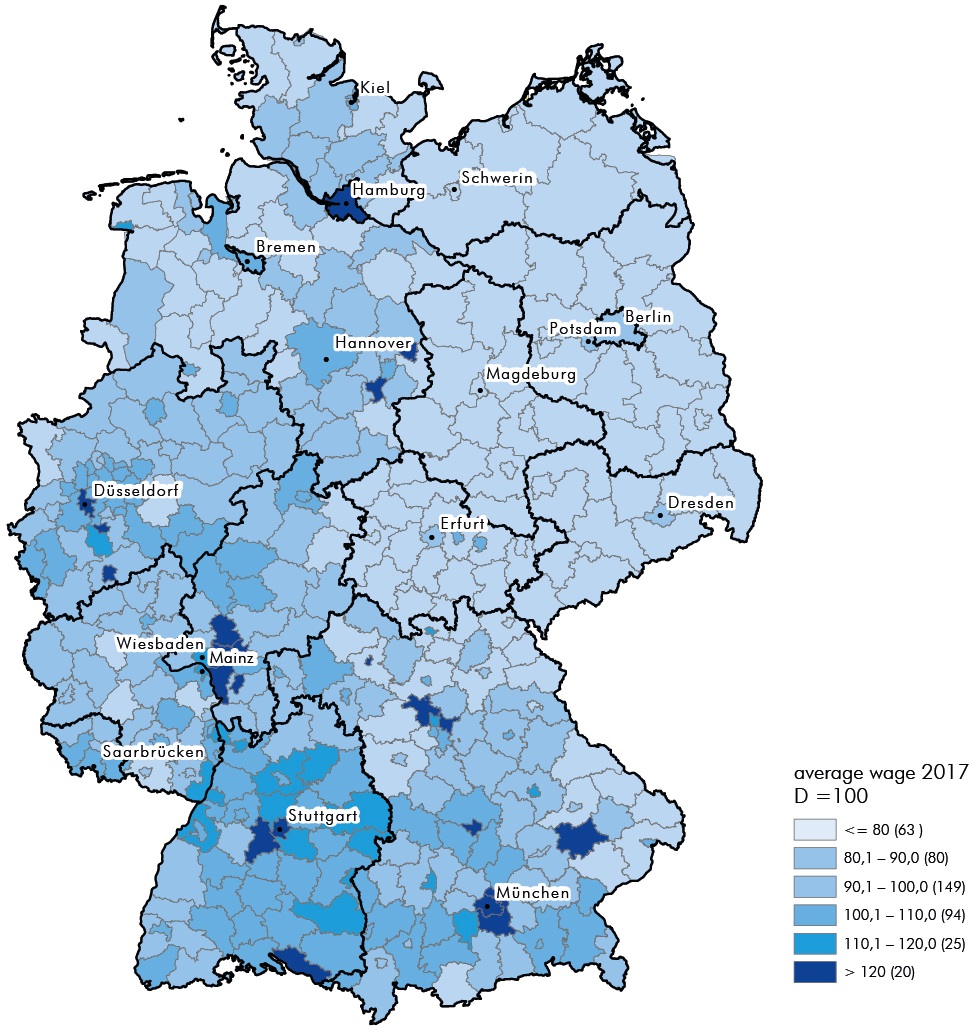

Average wage: clear east-west divide in salaries

Median of monthly gross wages of full-time employees liable to the social insurance system; Germany = 100, 31.12.2017

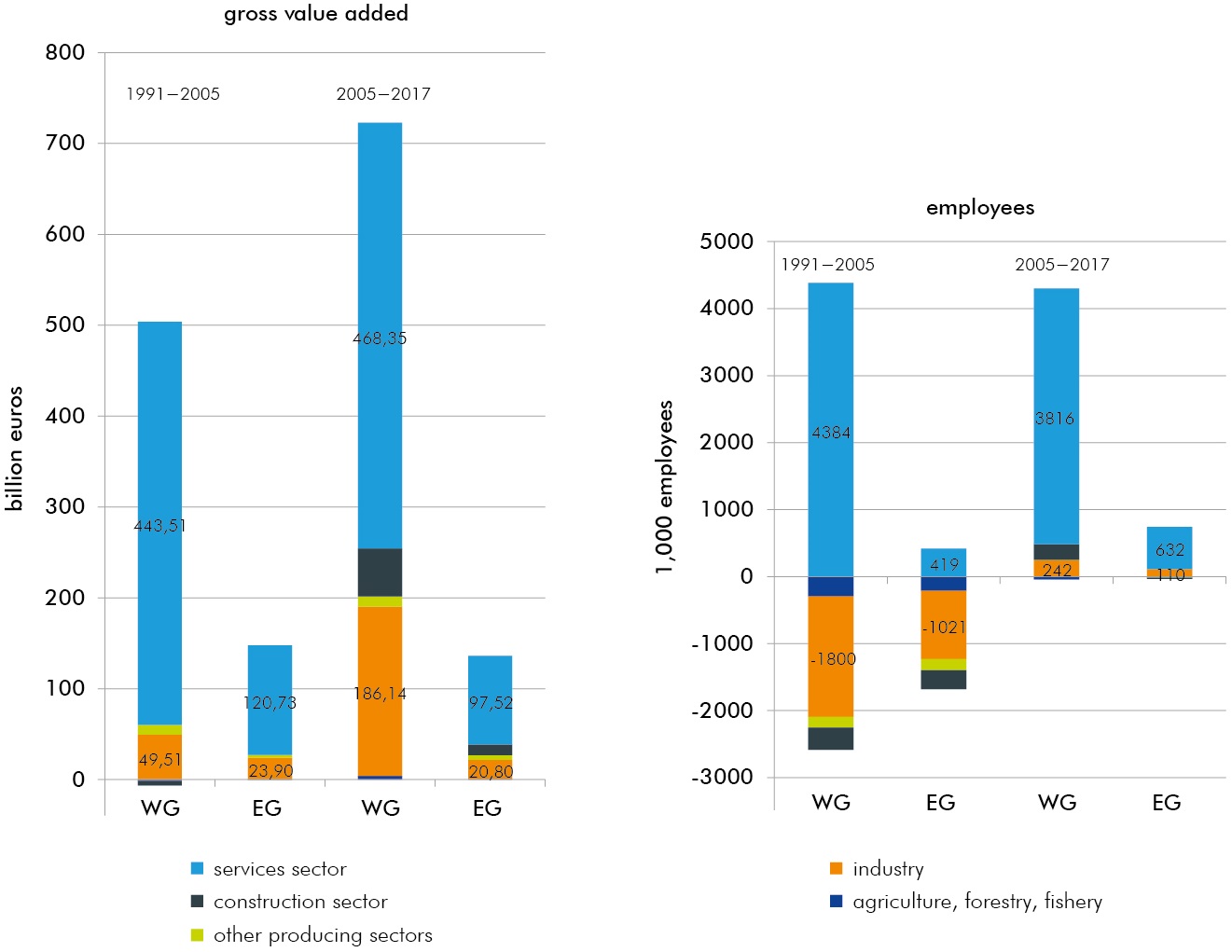

Services are the main source of added value and employment

Absolute change in gross value added in current prices and in employment by industries

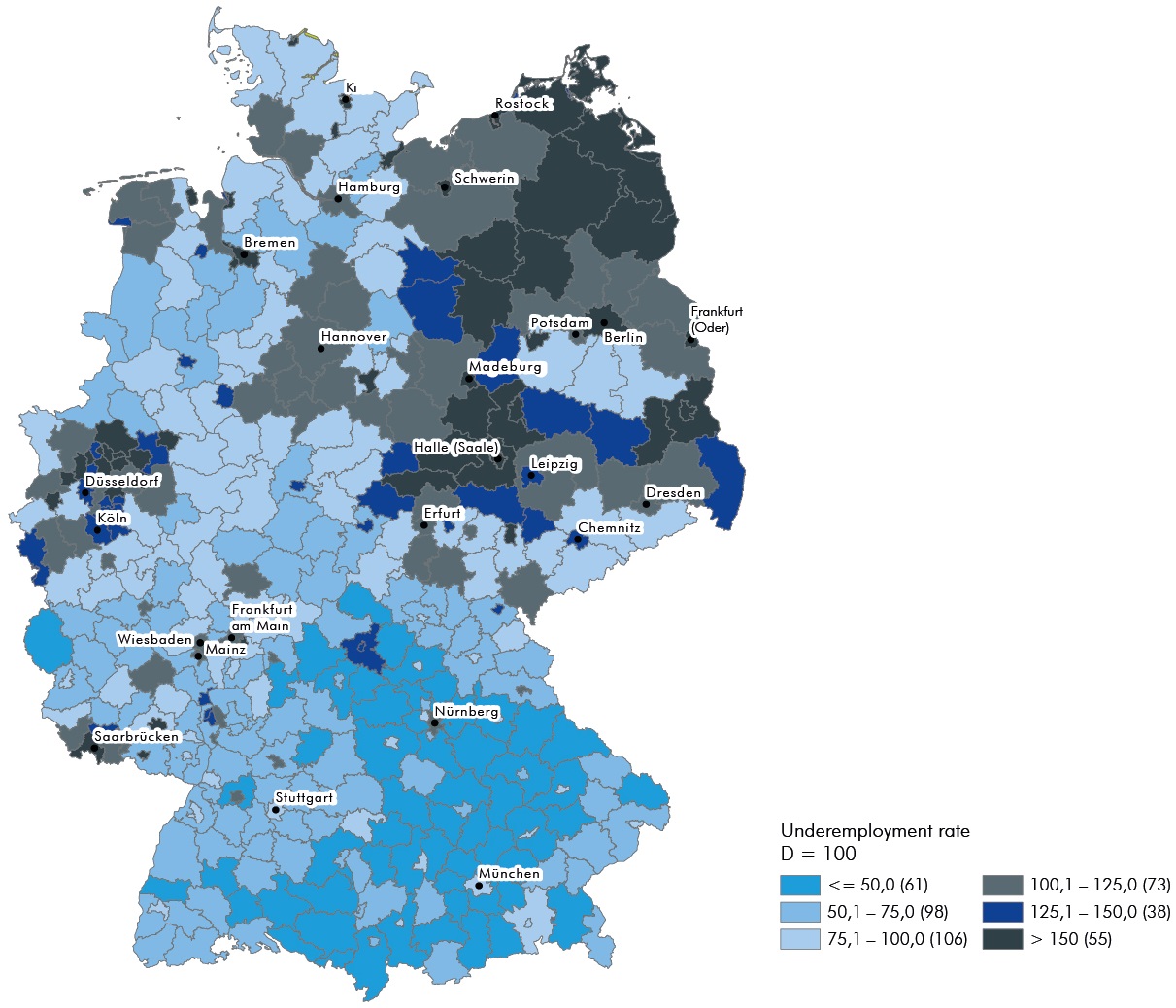

Underemployment rates: large regional differences

Underemployment quota in Germany = 100, 2017

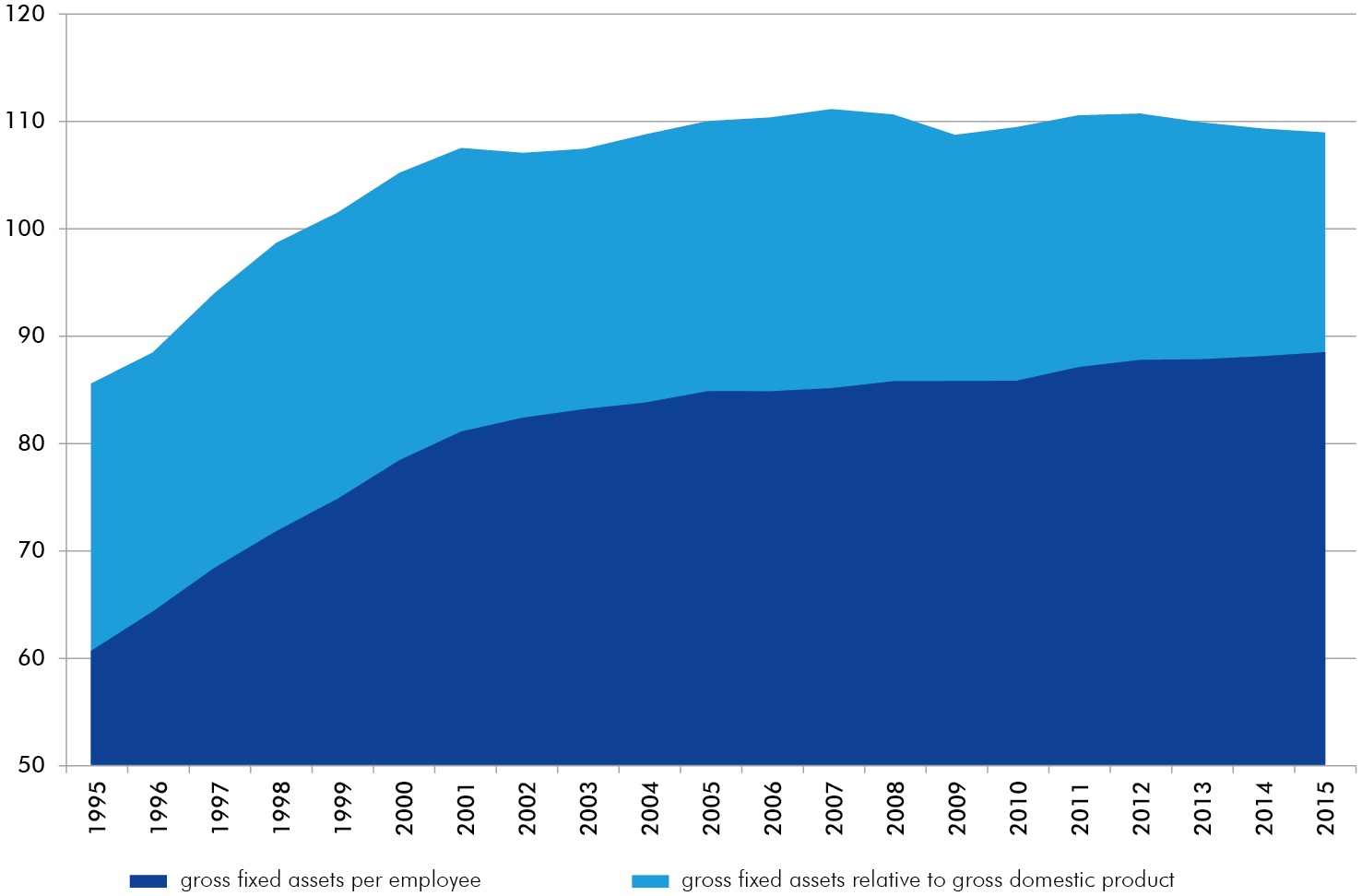

Lack of capital of no significance for East Germany‘s productivity shortfall

Gross fixed assets at replacement costs in East Germany including Berlin relative to West Germany, in %

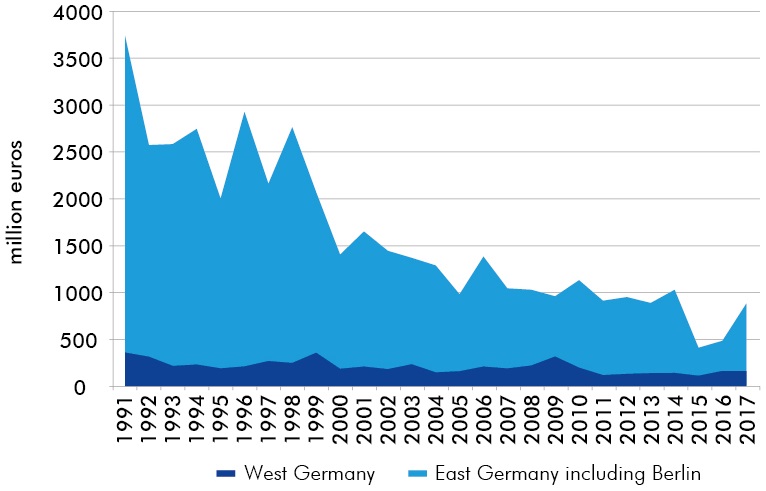

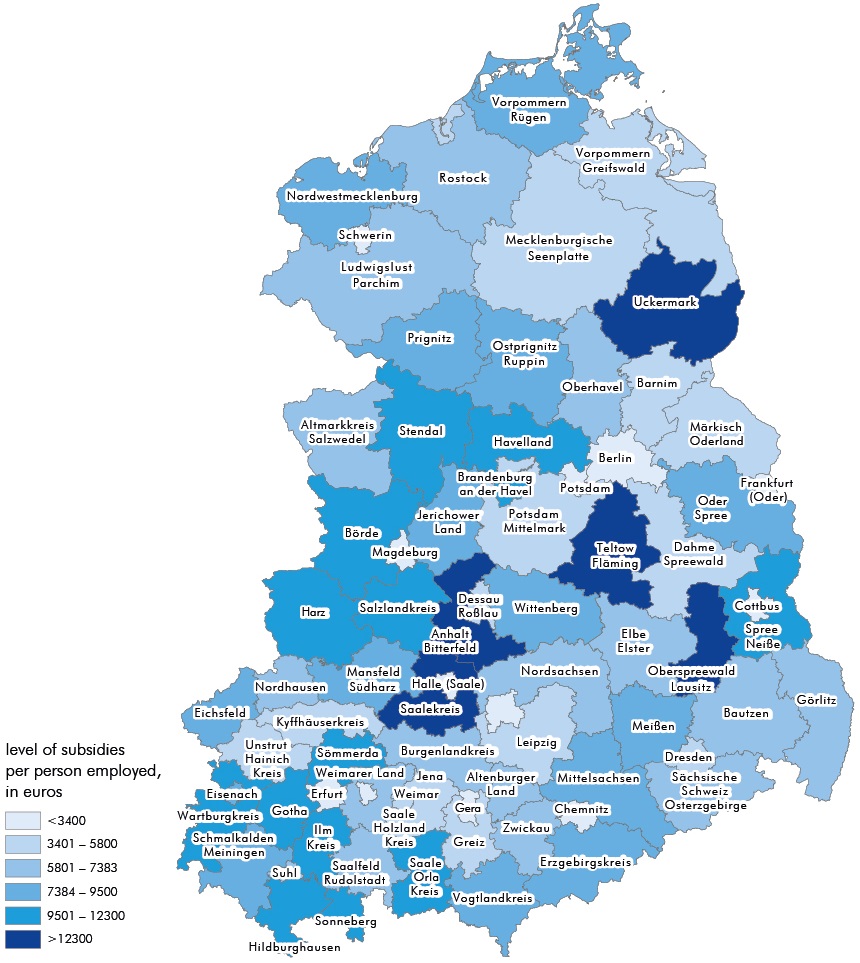

In East Germany, rural regions gained aboveaverage benefit from regional aid – but the period of generous subsidies is over

Investment grants to commercial businesses from 1991 to 2017

In East Germany, rural regions gained aboveaverage benefit from regional aid – but the period of generous subsidies is over

Investment grants to commercial businesses from 1991 to 2017

East-west migration: net emigration comes to a halt

Out-migration from East Germany to West Germany, in-migration to East Germany from West Germany, migration balance, from 1989 to 2015

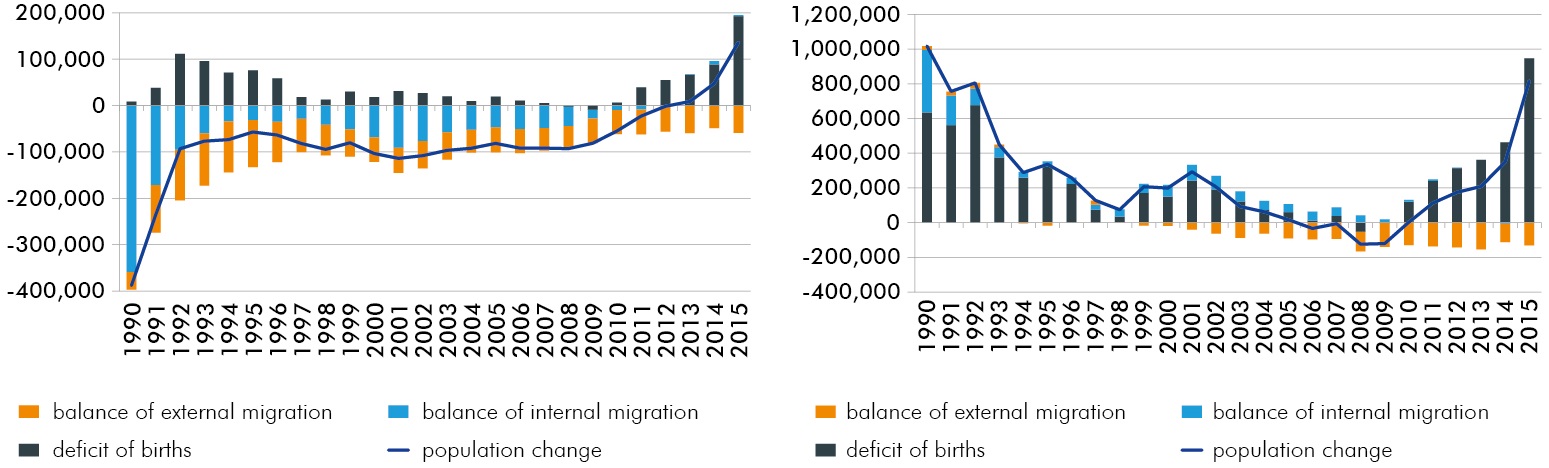

Population development in East Germany: an increase from 2013 onwards as a result of overseas migration gains

Population development in East and West Germany in the period from 1990 to 2015 by components, yearly population change (number of persons)

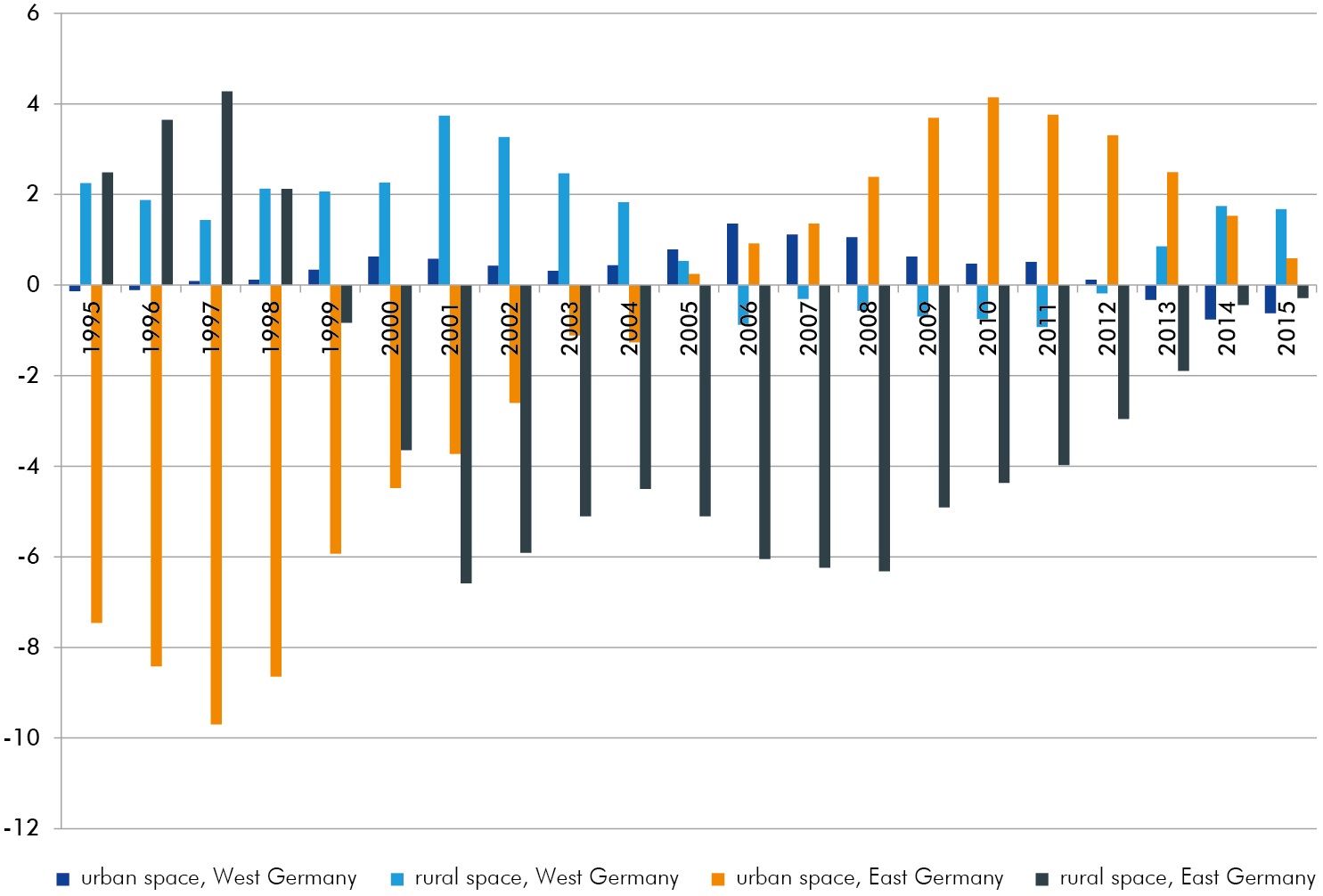

Internal migration: the population of rural areas in East Germany has continuously declined since 1999

Balance of internal migration per 1,000 inhabitants

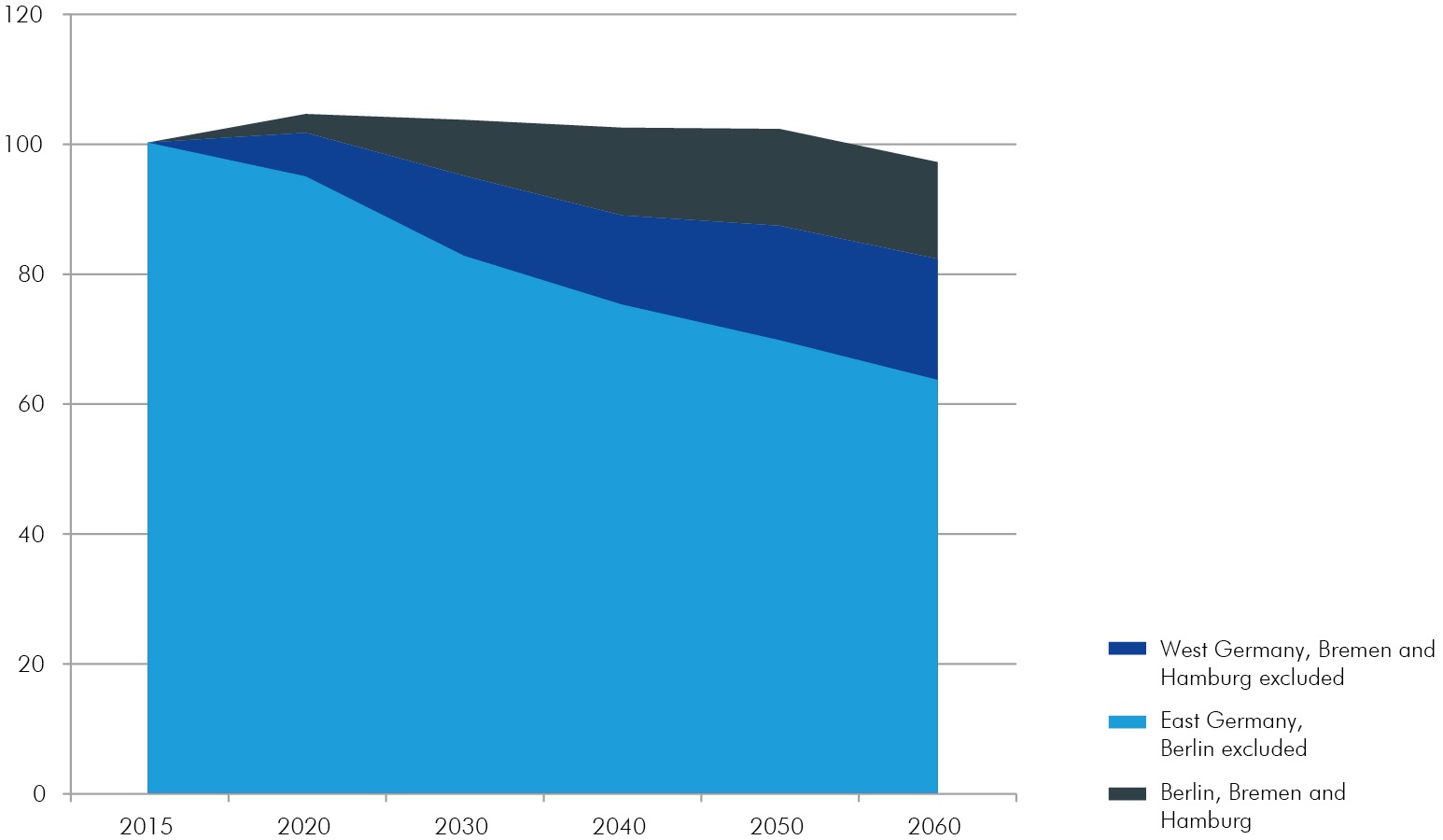

Decline in working-age population in East German territorial areas until 2060 more than twice as big as in West Germany

Index of development of population at employable age (20 up to below 67 years) based on the updated 13. coordinated population projection by the Federal Statistical Office, year 2015 = 100

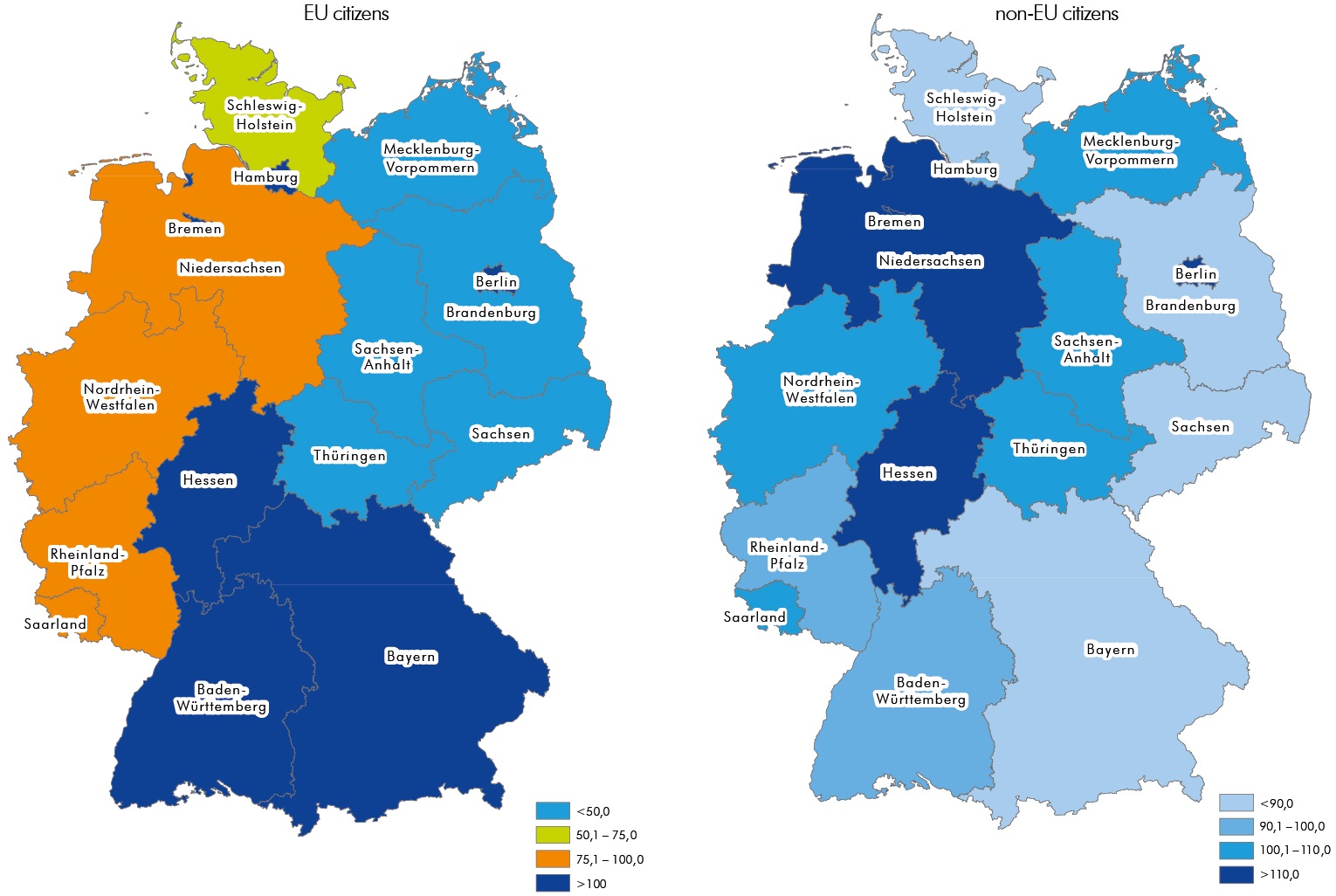

Migration gains from the EU: significantly lower in East Germany than in West Germany

Cumulative net migration gain per 1,000 inhabitants, Germany = 100

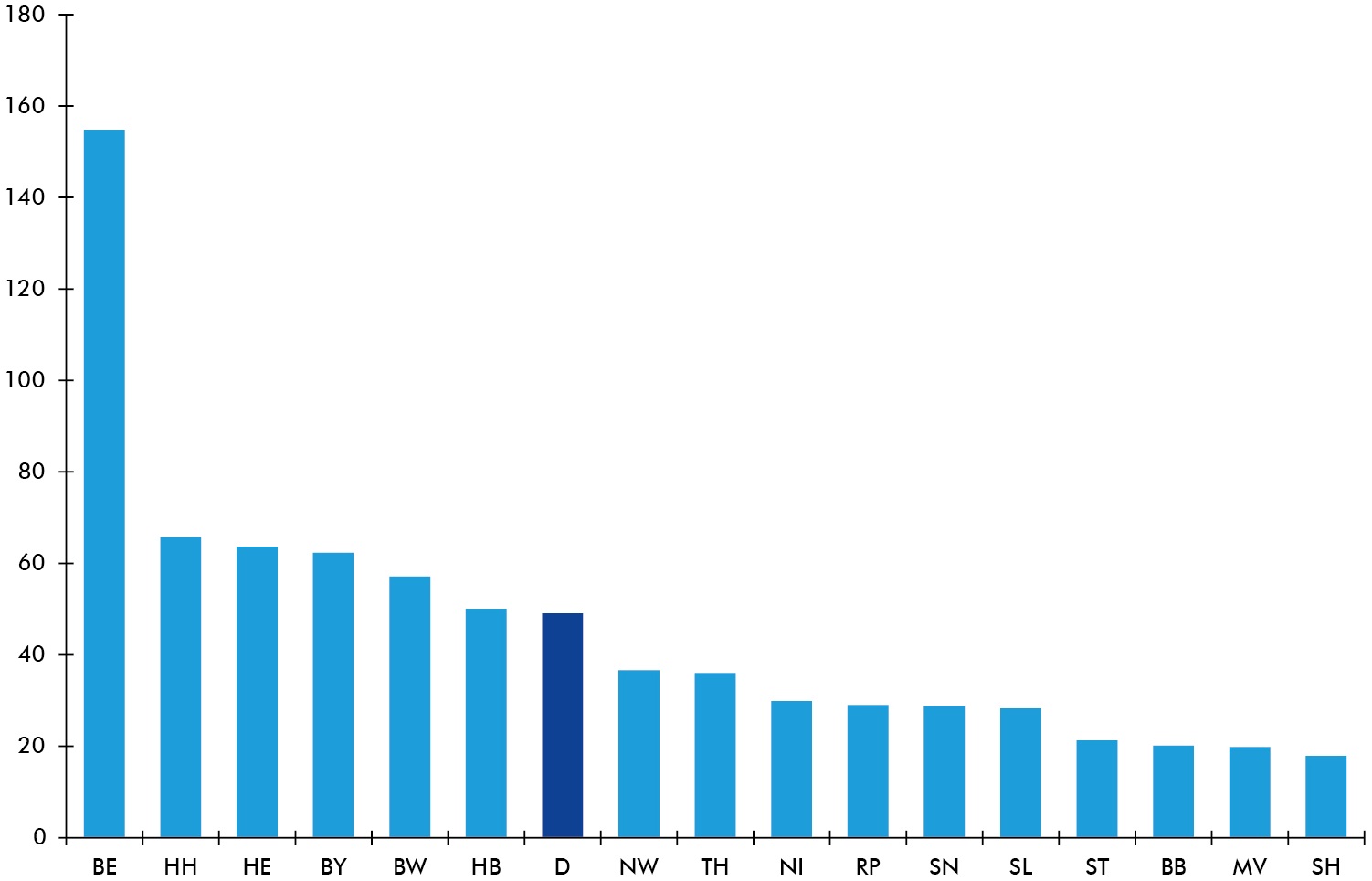

EU blue card: Berlin has a clear lead

Blue card recipients per 100,000 employees in the federal states in 2017

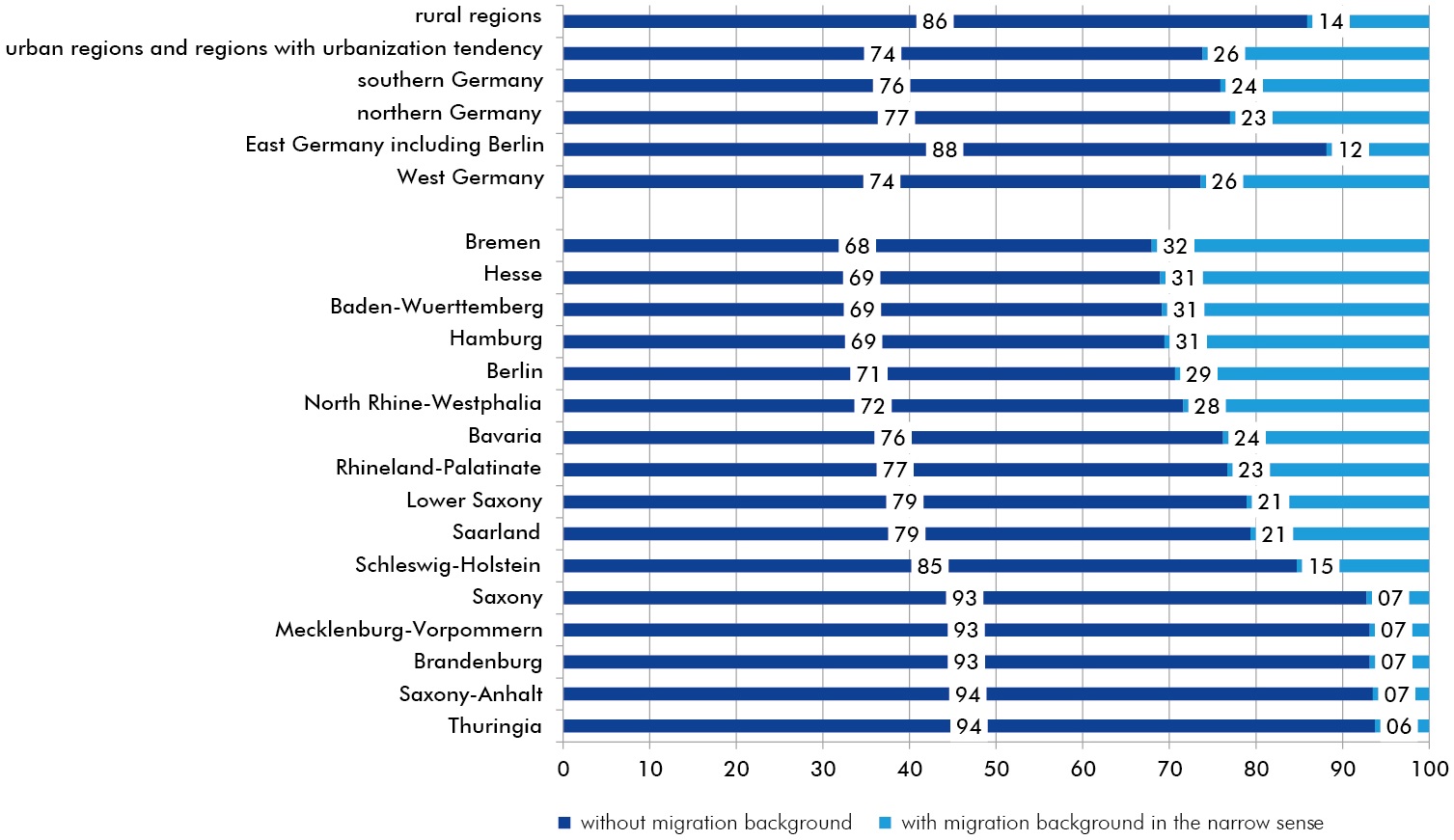

Proportion of people with a migrant background in East Germany and rural regions well below the federal average

Share of population without and with migration background in 2017 in % (total population = 100)

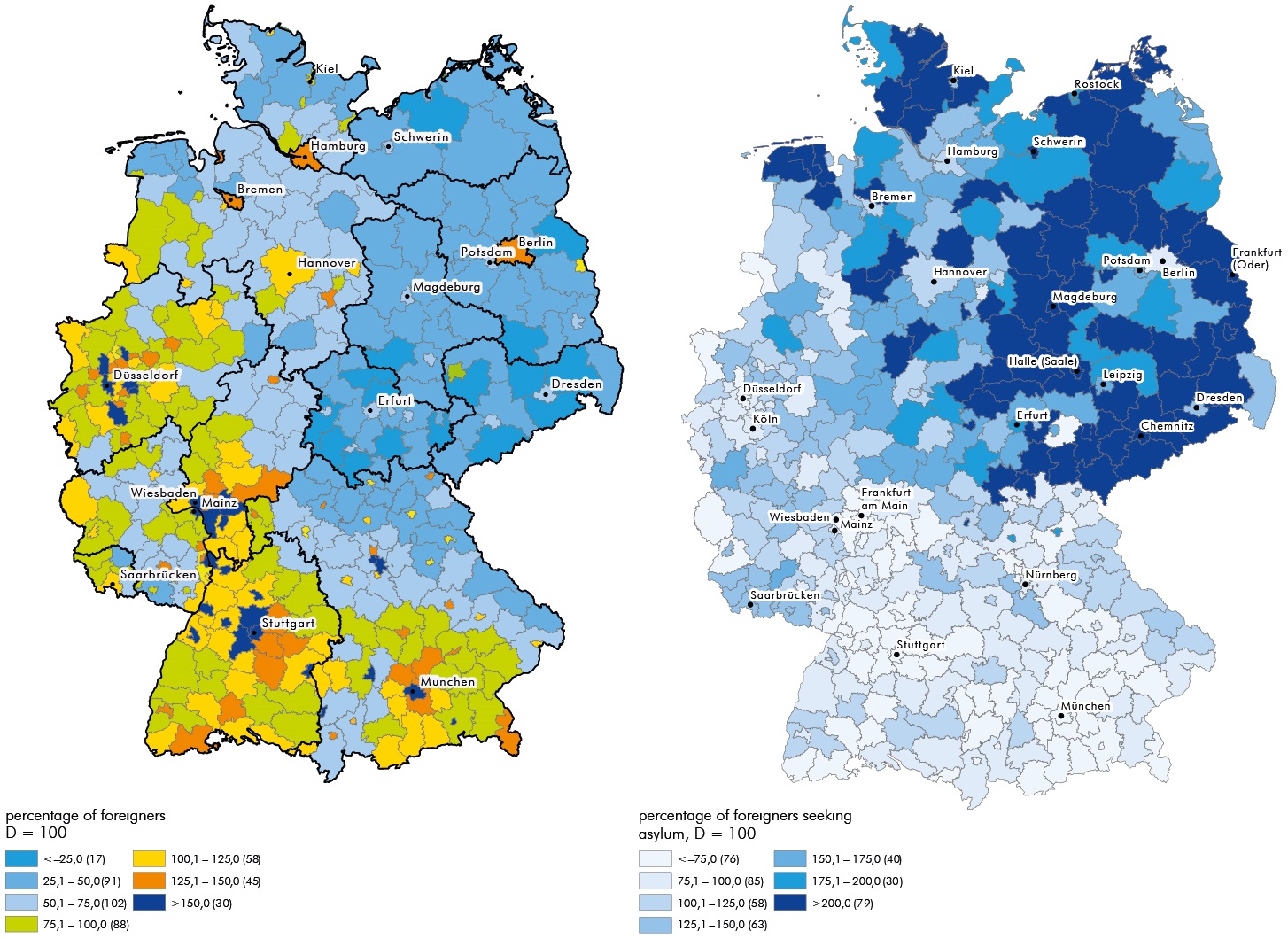

Percentage of foreigners seeking asylum: well above average percentage in East German territorial areas, with a lower percentage of foreigners

31.12.2016

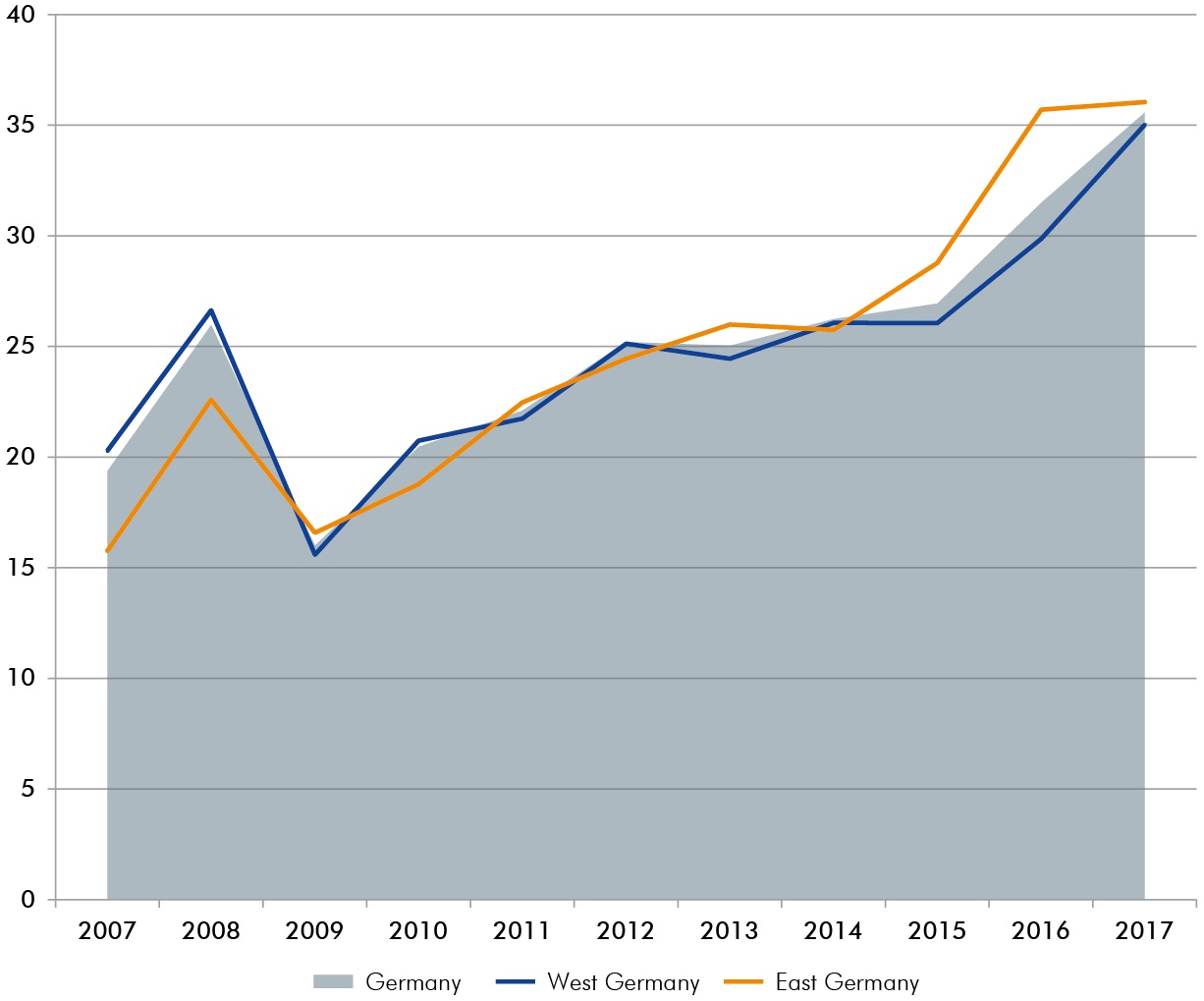

Specialist staff vacancies: a growing problem in East and West German companies

Vacancies, 2007 to 2017, in %

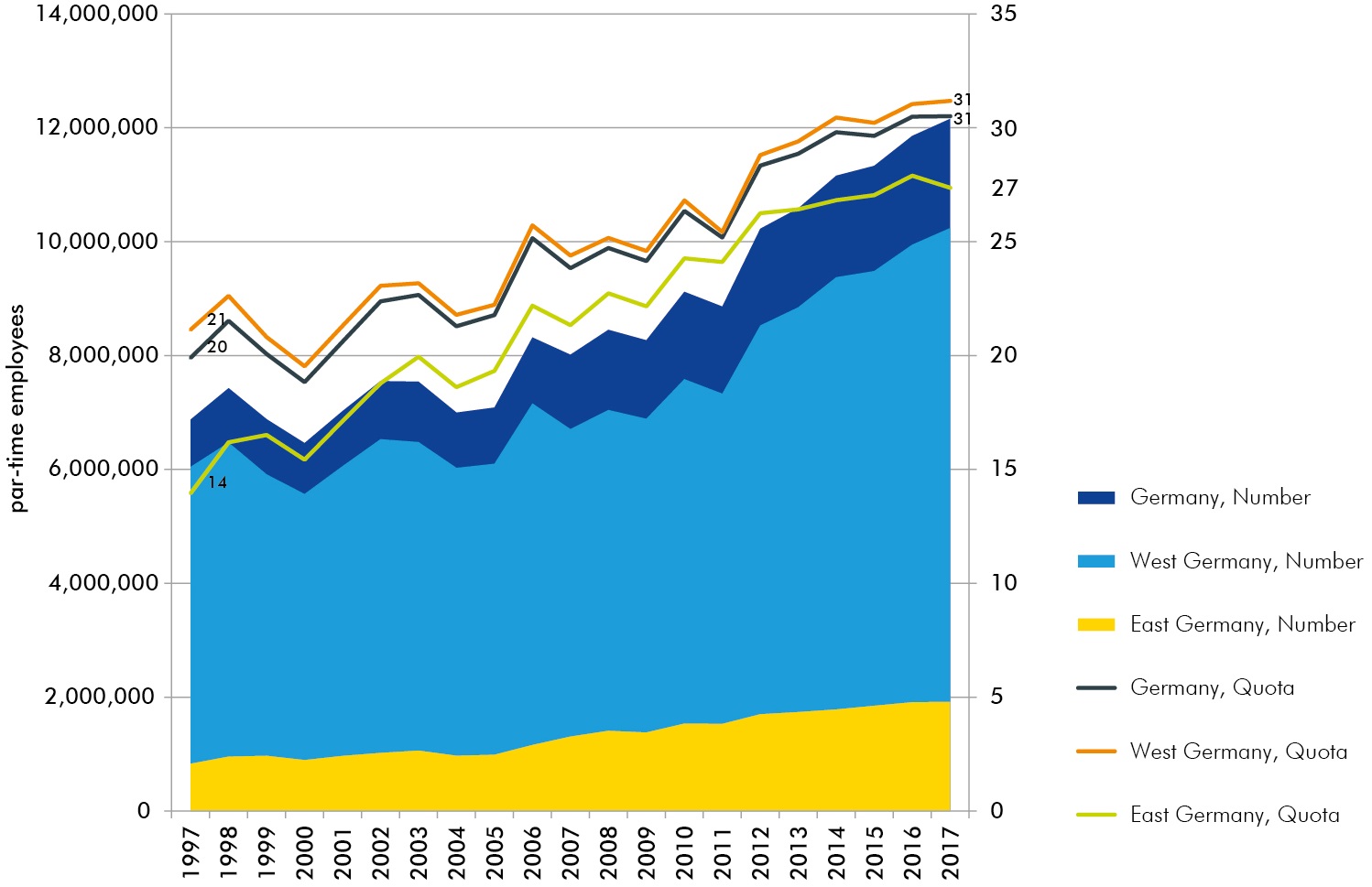

Part-time work: lower proportion of part-time staff in East Germany

Part-time employment and share of part-time employment in total employment, 1997 to 2017

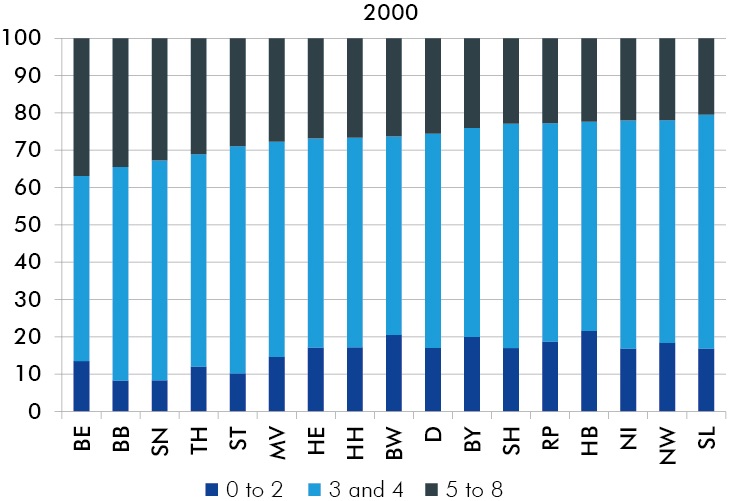

Tertiary education is falling behind in East German territorial areas

Employment in the federal states by education level, ranked by the share of employees with tertiary education

Tertiary education is falling behind in East German territorial areas

Employment in the federal states by education level, ranked by the share of employees with tertiary education

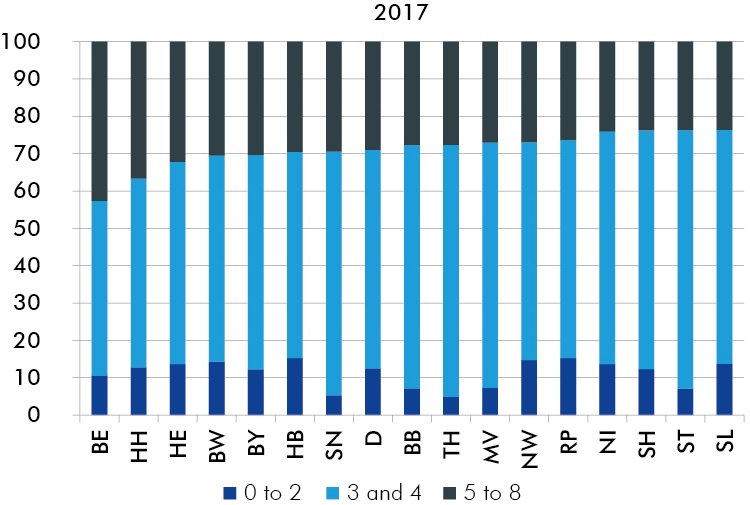

Large regional differences in school drop-outs

Early school leavers: share of school leavers who do not possess a Certificate of Secondary Education in the total number of school leavers in 2016, Germany = 100

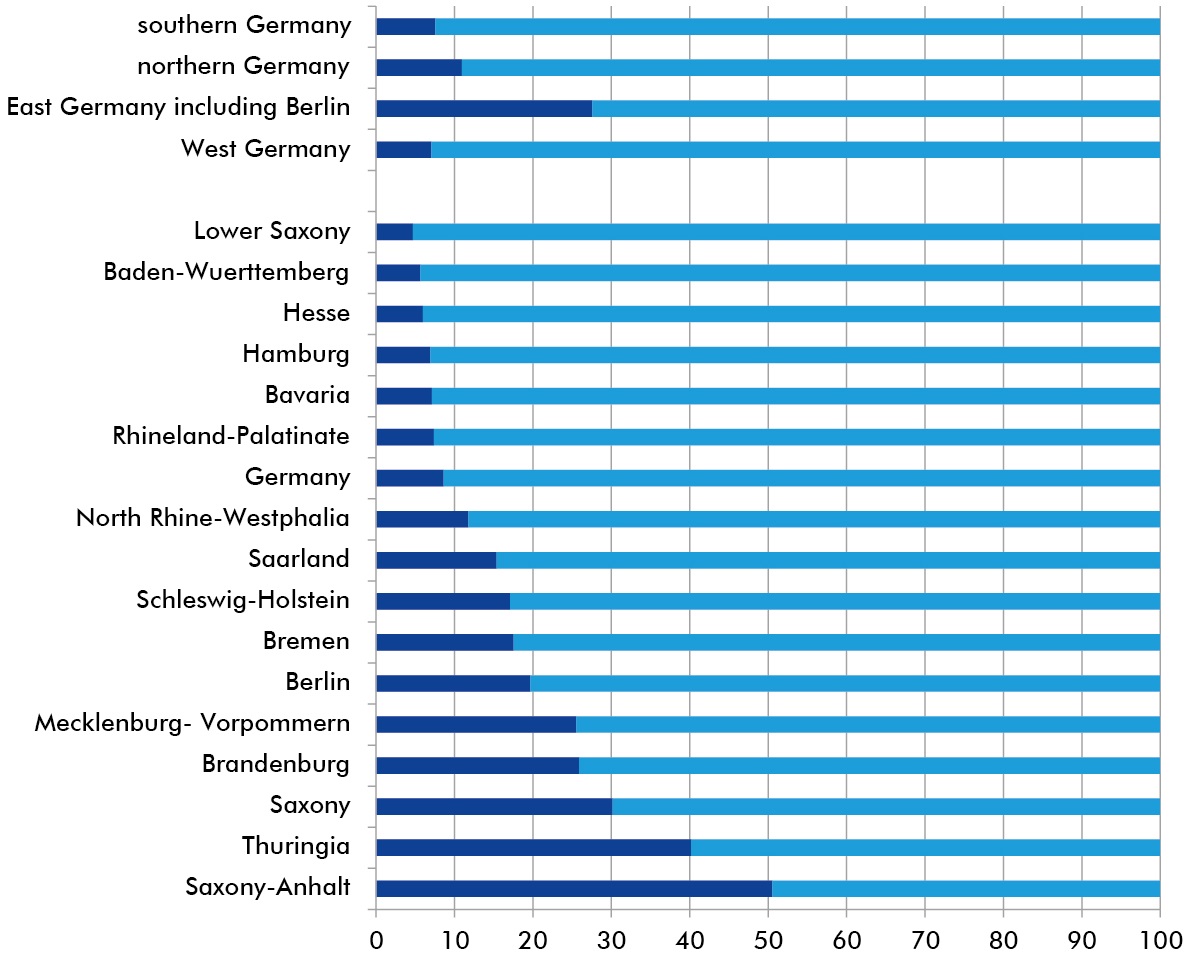

In East Germany and structurally weak West German states, SMEs make an above-average contribution to the economy‘s research and development spending

Internal R&D expenditures in the corporate sector by employment size of firms 2015, in % (total expenditures per state or region = 100)

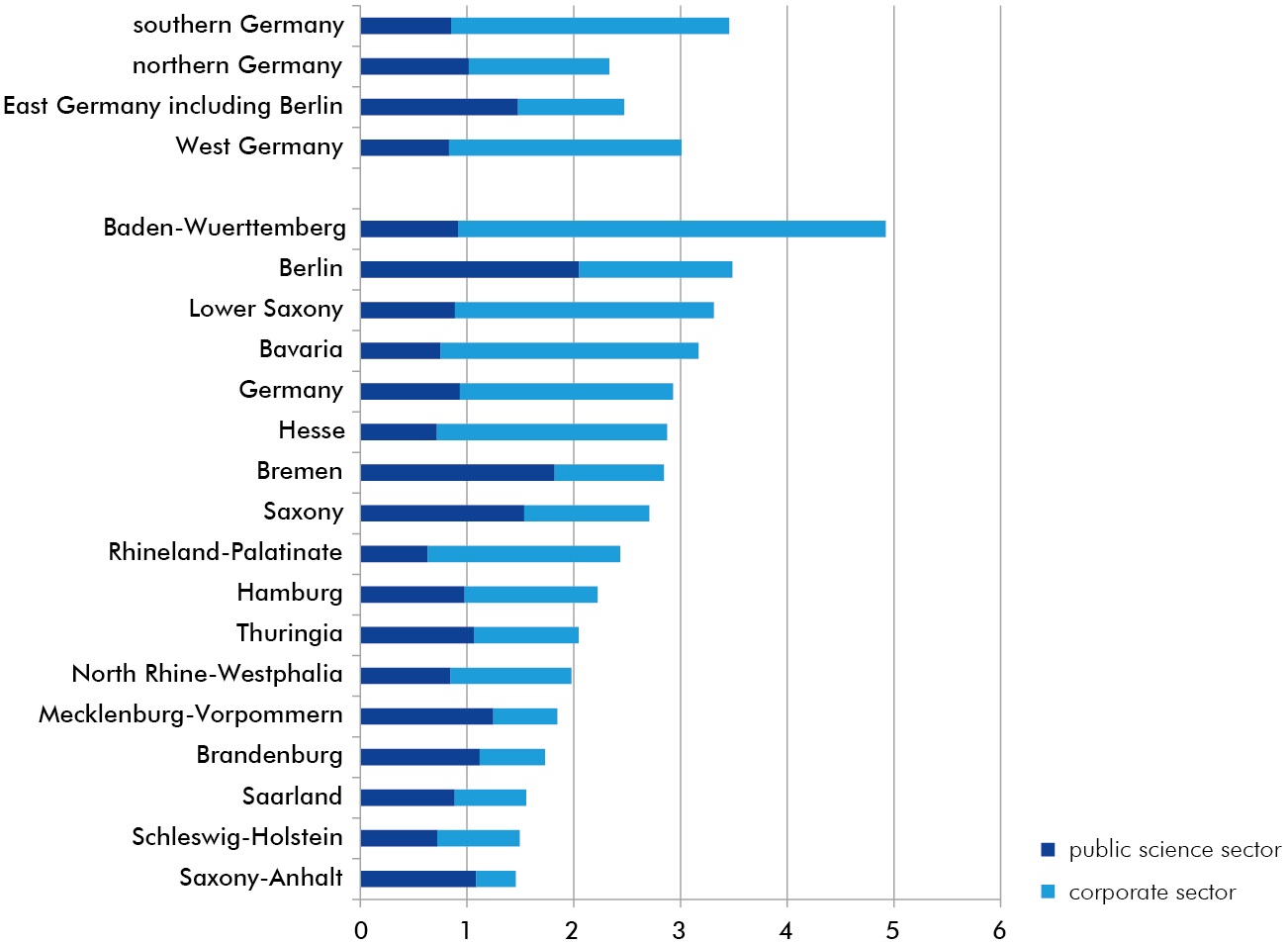

Baden-Wuerttemberg, Berlin, Lower Saxony and Bavaria spend above-average amounts on research and development

Share of internal R&D expenditures 2016 in gross domestic product by federal states and regions, current prices, in %

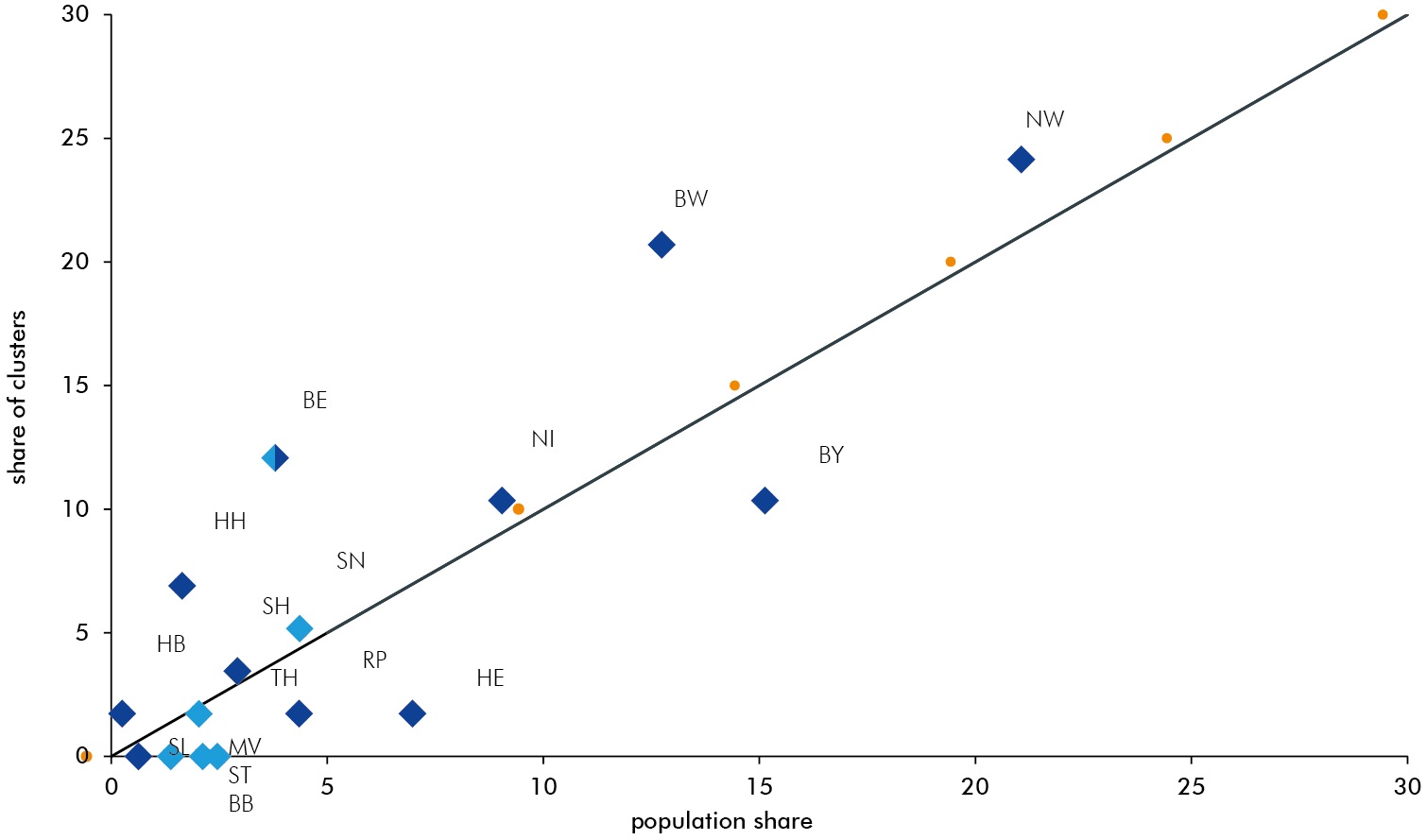

Excellence clusters: East German territorial areas underrepresented in cutting-edge research, with the exception of Saxony

Share of the federal states in the 57 excellence clusters of German universities in relation to the share in total population in Germany, in %

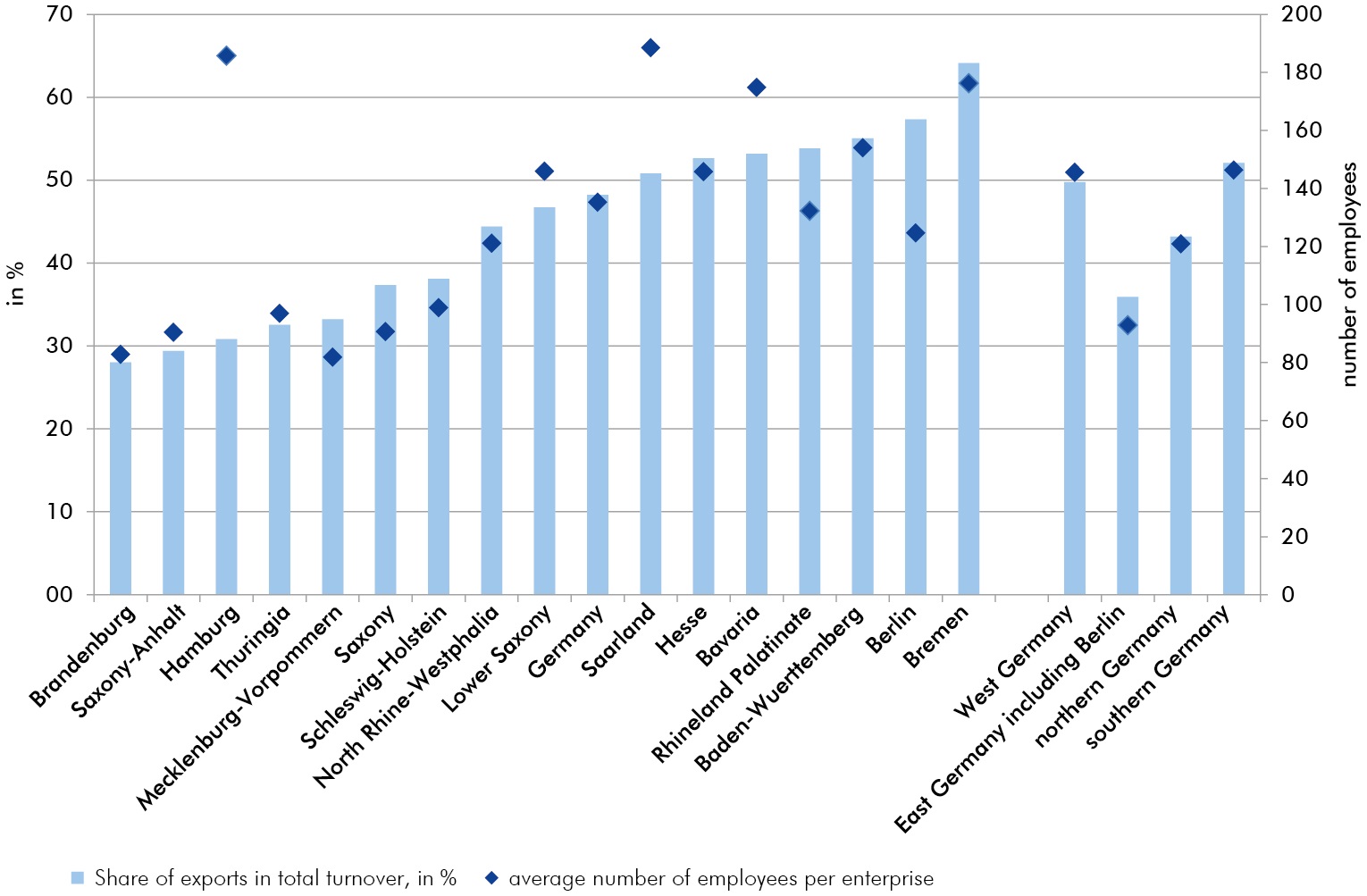

In industry, companies of below-average size tend to be associated with lower export rates

Employees per enterprise, share of exports in total turnover, 2017, enterprises belonging to firms of the manufacturing sector, mining and quarrying of 20 and more employees

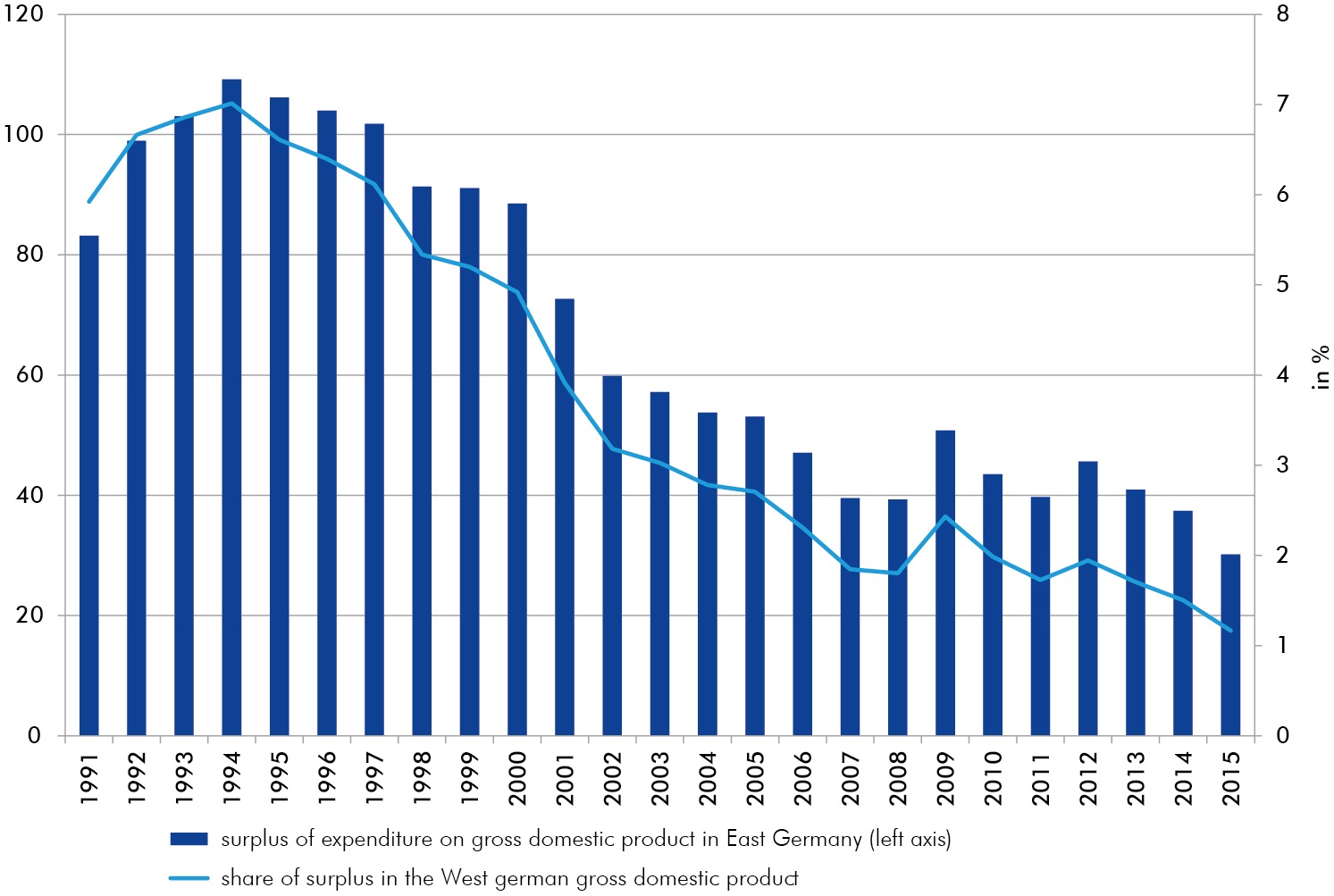

East Germany‘s transfer dependency has fallen, but still exists

Gap between expenditure and gross domestic product in East Germany including Berlin, absolute volume and relative to the GDP in West Germany

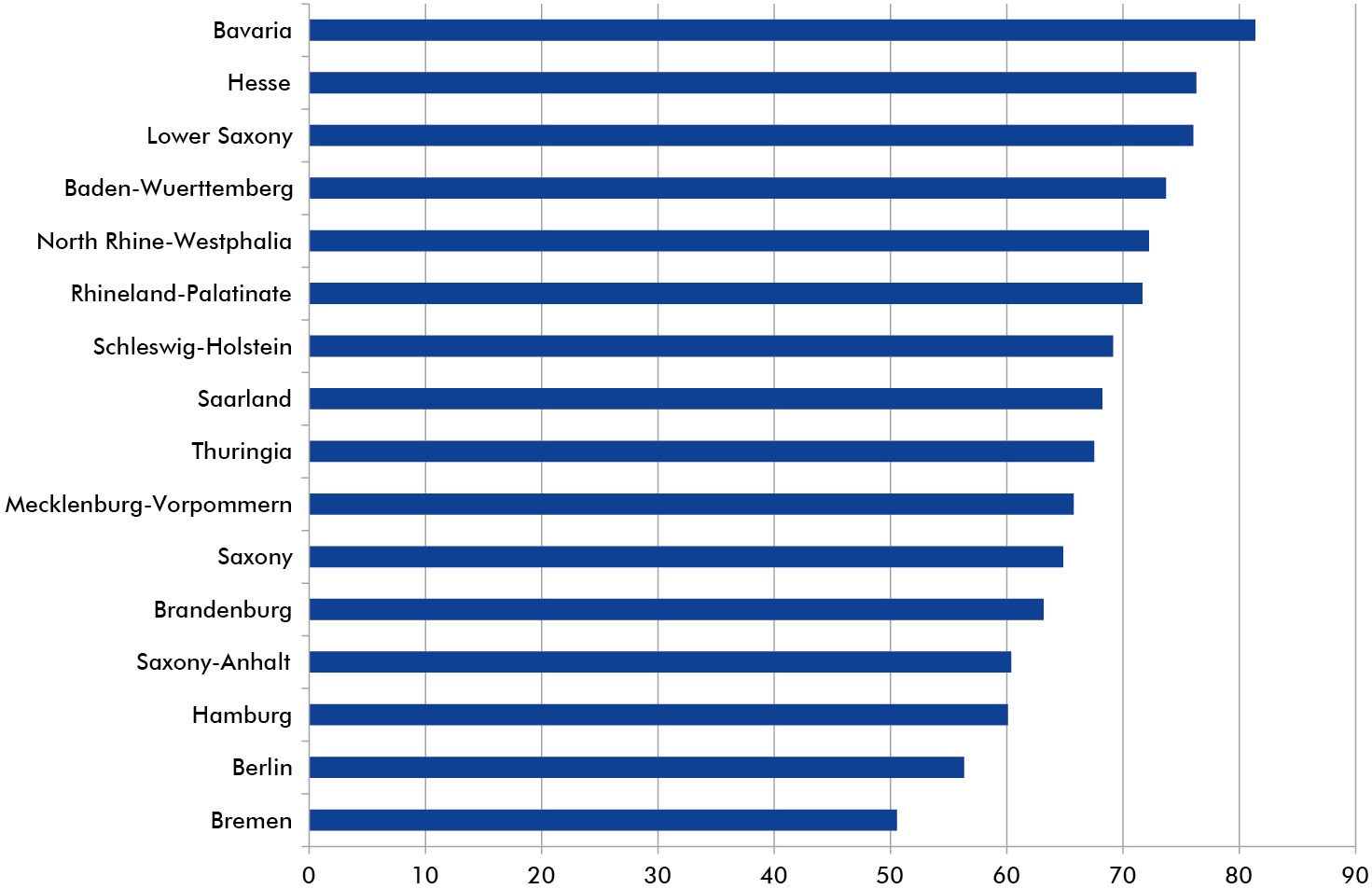

2017 tax coverage ratio: still an east-west divide

Tax revenues as a percentage of adjusted expenditures, in %

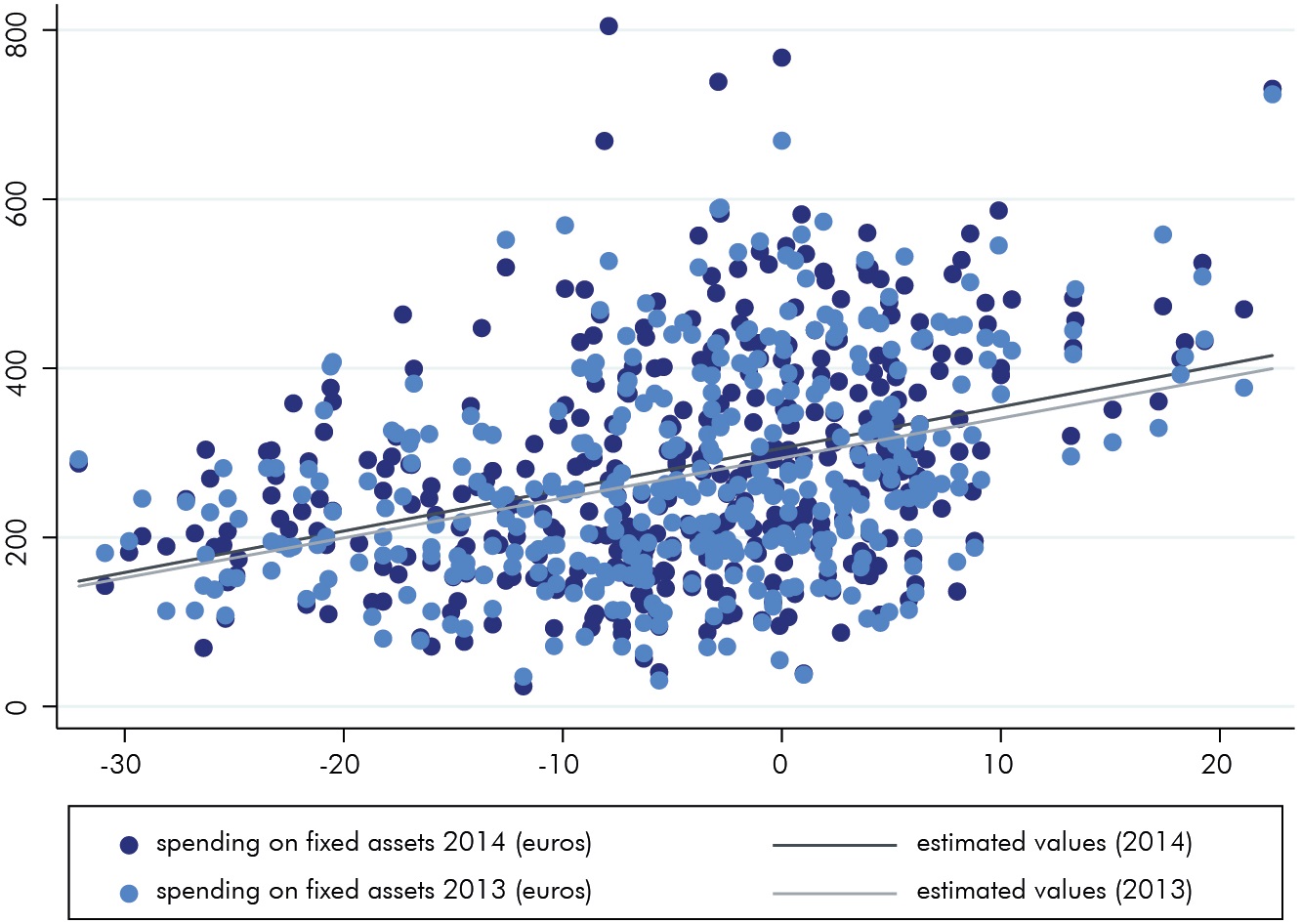

Not all municipalities anticipate demographic change in their investment decisions

Distribution of municipal investment in fixed assets per resident in Euro for the years 2013 and 2014

Publications on "East Germany"

Ostdeutschland - Eine Bilanz

in: One-off Publications, Festschrift für Gerhard Heimpold, IWH 2020

Abstract

Anlass dieser Festschrift ist die Verabschiedung von Dr. Gerhard Heimpold, dem stellvertretenden Leiter der Abteilung Strukturwandel und Produktivität am Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Halle (IWH), aus dem aktiven Berufsleben in den wohlverdienten Ruhestand. Gerhard Heimpold forschte am IWH zu Aspekten der Regionalentwicklung Ostdeutschlands unter Beachtung des politischen und wirtschaftlichen Transformationsprozesses. Er gehört heute zu den wenigen Experten in Deutschland, die umfassende ökonomische Kenntnis über den gesamten Verlauf des Transformationsprozesses der ostdeutschen Wirtschaft seit Mitte der 1980er Jahre vorweisen können. Gerhard Heimpold hat im Laufe seiner akademischen Ausbildung und seiner ersten wissenschaftlichen Tätigkeit tiefe Einblicke in die Ausgestaltung und Funktionsweise der sozialistischen Planwirtschaft der DDR erhalten und konnte dieses Wissen nach dem Mauerfall 1989 in wichtige wissenschaftliche Beiträge auf dem Gebiet der internationalen Transformationsforschung einbringen.

Mikrofundierte makroökonomische Resultate der ostdeutschen Transformationswirtschaft

in: Contribution to IWH Volume, Festschrift für Gerhard Heimpold, IWH 2020

Abstract

Mit zunehmend zeitlichem Abstand seit der Wiederentstehung eines vereinten Deutschlands schwindet im Alltag das Wissen und in Forschung und Lehre das Verständnis der bewegenden Kräfte um dieses historisch einmalige und bis in die Gegenwart nachwirkende Ereignis. Die Zeitzeugen und die Mitgestalter der damit verbundenen Transformation einer Zentralplanwirtschaft verlassen altersbedingt die Bühne, und die nachrückenden Generationen wenden sich anderen Herausforderungen zu. Denn heute stehen erneut, aber ganz anders geartete Transformationsprozesse auf der Tagesordnung: Gefragt sind Antworten auf den Klimawandel, den Ausstieg aus der Energiegewinnung durch fossile Brennstoffe, die Digitalisierung der Produktions- und Verbrauchsprozesse, die Verkehrswende und anderes. Schnell wird dann die Transformation einer ganzen Wirtschaftsordnung von der Agenda verdrängt, und die systemischen Zusammenhänge sowie das Verständnis der längerfristigen Folgen dieses historischen Wendepunktes für Deutschland treten in den Hintergrund und geben den Platz frei für oberflächliche Vereinfachungen. Der Systemwechsel verschwindet im sprachlichen Alltag hinter Schlagworten wie “Wende” und Ost-West-Vergleiche, in denen historische Bruchstellen geglättet bzw. sozioökonomische Inhalte durch die Projektion auf Himmelsrichtungen ersetzt werden. Selbstverständlichkeiten aus der Zeit des Umbruchs gehen unter oder werden durch Halbwahrheiten verzerrt wiedergegeben.

Die Entfaltung einer Marktwirtschaft – Die ostdeutsche Wirtschaft fünf Jahre nach der Währungsunion

in: Contribution to IWH Volume, Festschrift für Gerhard Heimpold, IWH 2020

Abstract

Die Öffnung der Mauer am 9. November 1989, die Einführung der Deutschen Mark (DM) in der DDR zum 1. Juli 1990, die Wiedervereinigung am 3. Oktober 1990: Diese drei Daten markieren vor dem Hintergrund des Zusammenbruchs des Sozialismus in Osteuropa eine historische Umwälzung, die nicht nur die politischen Verhältnisse in Deutschland grundlegend verändert hat, sondern auch eine neue deutsche Volkswirtschaft hervorbringen sollte. Das marktwirtschaftliche System, in dessen Ordnungsrahmen der Westen des Landes zu Wohlstand gekommen ist, würde nun – so waren die Erwartungen – auch im Osten des Landes eine dynamische Wirtschaftsentwicklung einleiten und die Mangel des sozialistischen Systems der DDR vergessen machen. Die Erwartungen waren hoch, ja euphorisch. Durch die Aufhebung aller Einfuhrbeschränkungen und die Ausstattung der DDR-Bürger mit konvertibler DM wurden lange aufgestaute Konsumwünsche rasch erfüllbar. Weil nicht mehr wie zuvor chronische Materialengpässe immer wieder Produktionsstillstand verursachen würden, konnte ein sprunghafter Effizienzzuwachs in der Produktion erwartet werden. Das Unternehmertum, in der DDR systematisch eingeengt und bis zur volkswirtschaftlichen Bedeutungslosigkeit reduziert, würde sich entfalten und für Arbeitsplätze und steigende Einkommen sorgen. Angesichts des Nachholbedarfs an Modernisierung im Maschinenpark und in der Infrastruktur versprachen Investitionen im Osten eine hohe Rentabilität; das musste einen reichlichen Zustrom auswärtigen Kapitals auslösen. Zwar würde der Übergang vom Sozialismus zur Marktwirtschaft auch Lasten verursachen, aber nach verbreiteter Auffassung war nur eine „Anschubfinanzierung“ als finanzielle Unterstützung für den Osten durch den Westen nötig. Skeptische Stimmen, die in Ostdeutschland keine signifikanten Standortvorteile entdecken konnten und deswegen einen schmerzhaften Transformationsprozess erwarteten, gab es auch, doch wollte ihnen kaum jemand Gehör schenken. Zu sehr waren die Hoffnungen auf wirtschaftlichen Wohlstand ausgerichtet; die Befreiung von jahrzehntelanger staatlicher Bevormundung und Einschränkung stärkte die Einschätzung, dass das Erhoffte mit entsprechender Anstrengung auch erreichbar ist. Der „Aufholprozess“ – der Abbau des Einkommensrückstandes gegenüber Westdeutschland – schien nur eine Angelegenheit von wenigen Jahren zu sein.

Der Produktivitätsrückstand der ostdeutschen Industrie: Nur eine Frage der Preise?

in: Contribution to IWH Volume, Festschrift für Gerhard Heimpold, IWH 2020

Abstract

Die volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnung zeigt auch knapp drei Jahrzehnte nach der Deutschen Einheit, dass die Arbeitsproduktivität in Ostdeutschlands Industrie mehr als 20% unter dem westdeutschen Niveau verharrt. In dieser Arbeit gehe ich der Frage nach, ob dieser Rückstand die Folge einer geringeren physischen Produktivität oder niedrigerer Preise für ostdeutsche Erzeugnisse ist. Dazu werden Mikrodaten auf Firmenebene benutzt, die Informationen zu produzierten Gütermengen und erzielten Preisen enthalten. Der Rückstand in der Erlösproduktivität wird auch mit diesen Daten bestätigt. Die Hauptergebnisse sind, dass i) ostdeutsche Industrieunternehmen tatsächlich deutlich geringere Marktpreise erlösen und ii) der physische Output bei gleichen Inputmengen im Osten höher liegt als im Westen. Eine naheliegende Erklärung für beide Befunde ist, dass ostdeutsche Produkte weniger Kundennutzen generieren und gleichzeitig in weniger aufwändigen Produktionsverfahren hergestellt werden können. Weitere Tests zeigen, dass iii) die Hypothese verlängerter Werkbänke keine Erklärung für den ostdeutschen Produktivitätsrückstand ist und iv) ostdeutsche Betriebe im Vergleich zur westdeutschen Konkurrenz eine geringere physische Produktivität aufweisen, wenn sie Güter zu westdeutschen Preisen herstellen.

Regionale Disparitäten in Demographie und Migration — Ein Rückblick aus ostdeutscher Perspektive

in: Contribution to IWH Volume, Festschrift für Gerhard Heimpold, IWH 2020

Abstract

Ostdeutschland schrumpft, Westdeutschland wächst. Dieser Eindruck drängt sich aus demographischer Sicht auf, wenn die Bevölkerungsentwicklung seit 1989 betrachtet wird. Lebten auf dem Gebiet der fünf östlichen Bundesländer Ende 1988 noch 15,4 Millionen Personen, so waren es Ende 2018 nur 12,6 Millionen Personen – ein Rückgang um fast drei Millionen Einwohner oder beinahe 20%. Die zehn westlichen Bundesländer wuchsen im selben Zeitraum von 59,6 Millionen auf 66,8 Millionen Einwohner. Der überwiegende Teil dieser unterschiedlichen demographischen Entwicklung ist der räumlichen Umverteilung von Bevölkerung geschuldet, einerseits der Nettobinnenwanderung von Ost- nach Westdeutschland, andererseits der sehr unterschiedlichen Verteilung der Nettoaußenwanderungen. Die Umverteilung der Bevölkerung ist dabei nicht homogen, vielmehr in starkem Maße selektiv – vor allem in den Dimensionen von Ausbildung, Alter, Geschlecht und Nationalität.