Productivity: More with Less by Better

Available resources are scarce. To sustain our society's income and living standards in a world with ecological and demographic change, we need to make smarter use of them.

Dossier

In a nutshell

Nobel Prize winners Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus state in their classic economics textbook: Economics matters because resources are scarce. Indeed, productivity research is at the very heart of economics as it describes the efficiency with which these scarce resources are transformed into goods and services and, hence, into social wealth. If the consumption of resources is to be reduced, e. g., due to ecological reasons, our society’s present material living standards can only be maintained by productivity growth. The aging of our society and the induced scarcity of labour is a major future challenge. Without productivity growth a solution is hard to imagine. To understand the processes triggering productivity growth, a look at micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments is indispensable.

Our experts

Department Head

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-708 Request per E-Mail

President

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-700 Request per E-MailAll experts, press releases, publications and events on “Productivity”

Productivity is output in relation to input. While the concept of total factor productivity describes how efficiently labour, machinery, and all combined inputs are used, labour productivity describes value added (Gross Domestic Product, GDP) per worker and measures, in a macroeconomic sense, income per worker.

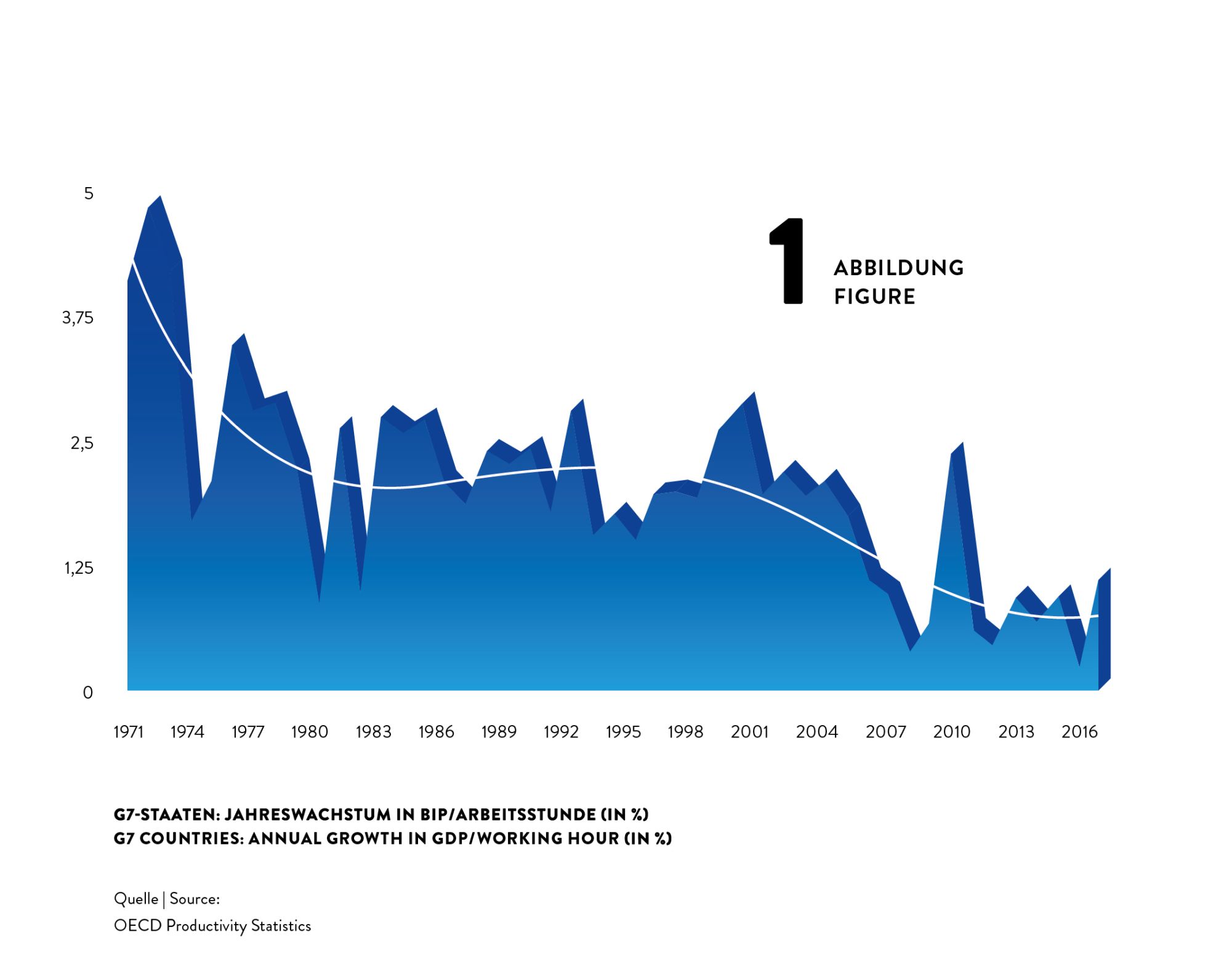

Productivity Growth on the Slowdown

Surprisingly, despite of massive use of technology and rushing digitisation, advances in productivity have been slowing down during the last decades. Labour productivity growth used to be much higher in the 1960s and 1970s than it is now. For the G7 countries, for example, annual growth rates of GDP per hour worked declined from about 4% in the early 1970s to about 2% in the 1980s and 1990s and then even fell to about 1% after 2010 (see figure 1).

This implies a dramatic loss in potential income: Would the 4% productivity growth have been sustained over the four and a half decades from 1972 to 2017, G7 countries’ GDP per hour would now be unimaginable 2.5 times as high as it actually is. What a potential to, for instance, reduce poverty or to fund research on fundamentals topics as curing cancer or using fusion power!

So why has productivity growth declined dramatically although at the same time we see, for instance, a boom in new digital technologies that can be expected to increase productivity growth? For sure, part of the decline might be spurious and caused by mismeasurement of the contributions of digital technologies. For instance, it is inherently difficult to measure the value of a google search or another video on youtube. That being said, most observers agree that part of the slowdown is real.

Techno-Pessimists and Techno-Optimists

Techno-pessimists say, well, these new technologies are just not as consequential for productivity as, for instance, electrification or combustion engines have been. Techno-optimists argue that it can take many years until productivity effects of new technologies kick in, and it can come in multiple waves. New technology we have now may just be the tools to invent even more consequential innovations in the future.

While this strand of the discussion is concerned with the type of technology invented, others see the problem in that inventions nowadays may diffuse slowly from technological leaders to laggards creating a wedge between few superstar firms and the crowd (Akcigit et al., 2021). Increased market concentration and market power by superstar firms may reduce competitive pressure and the incentives to innovate.

Finally, reduced Schumpeterian business dynamism, i.e. a reduction in firm entry and exit as well as firm growth and decline, reflects a slowdown in the speed with which production factors are recombined to find their most productive match.

While the explanation for and the way out of the productivity puzzle are still unknown, it seems understood that using granular firm level data is the most promising path to find answers.

What are the Origins of Productivity Growth?

Aggregate productivity growth can originate from (i) a more efficient use of available inputs at the firm level as described above or (ii) from an improved allocation of resources between firms.

Higher efficiency at the firm level captures, e.g., the impact of innovations (Acemoglu et al., 2018) or improved firm organisation (management) (Heinz et al., 2020; Müller und Stegmaier, 2017), while improved factor allocation describes the degree of which scarce input factors are re-allocated from inefficient to efficient firms (‘Schumpeterian creative destruction’) (Aghion et al., 2015; Decker et al., 2021).

Most economic processes influence the productivity of existing firms and the growth and the use of resources of these firms and their competitors as well. The accelerated implementation of robotics in German plants (Deng et al., 2020), the foreign trade shocks induced by the rise of the Chinese economy (Bräuer et al., 2019), but also the COVID-19 pandemic, whose consequences are still to evaluate (Müller, 2021) not only effects on productivity and growth of the firms directly affected but at the same time may create new businesses and question existing firms.

While productivity can be measured at the level of aggregated sectors or economies, micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments are indispensable to study firm organisation, technology and innovation diffusion, superstar firms, market power, factor allocation and Schumpeterian business dynamism. The IWH adopts this micro approach within the EU Horizon 2020 project MICROPROD as well as with the CompNet research network.

As “creative destruction” may also negatively affect the persons involved (e. g., in the case of layoffs, Fackler et al., 2021), the IWH analyses the consequences of bankruptcies in its Bankruptcy Research Unit and looks at the implications of creative destruction for the society, e. g., within a project funded by Volkswagen Foundation searching for the economic origins of populism and in the framework of the Institute for Research on Social Cohesion.

Publications on “Productivity”

Aktuelle Trends: Ertragslage der ostdeutschen Betriebe verbessert sich stetig

in: Wirtschaft im Wandel, No. 3, 2017

Abstract

Ostdeutschland weist auch mehr als 25 Jahre nach der deutschen Vereinigung eine um circa ein Viertel geringere Arbeitsproduktivität als Westdeutschland auf. Wesentlich geringer ist der Rückstand jedoch bei der Ertragslage. Vor elf Jahren machten etwa 70% der westdeutschen Betriebe und 65% der ostdeutschen Betriebe Gewinne. Nach einem kurzen Knick um die Wirtschafts- und Finanzkrise 2009 ist dieser Anteil kontinuierlich auf 80% im Westen und 76% im Osten angestiegen. Das bedeutet, dass sich beide Landesteile bei dieser Kennzahl seit geraumer Zeit mit recht geringem Abstand im Gleichschritt bewegen.

The Dynamic Effects of Works Councils on Plant Productivity: First Evidence from Panel Data

in: British Journal of Industrial Relations, No. 2, 2017

Abstract

We estimate dynamic effects of works councils on labour productivity using newly available information from West German establishment panel data. Conditioning on plant fixed effects and control variables, we find negative productivity effects during the first five years after council introduction but a steady and substantial increase in the councils’ productivity effect thereafter. Our findings support a causal interpretation for the positive correlation between council existence and plant productivity that has been frequently reported in previous studies.

Declining Dynamism, Allocative Efficiency, and the Productivity Slowdown

in: American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, No. 5, 2017

Abstract

A large literature documents declining measures of business dynamism including high-growth young firm activity and job reallocation. A distinct literature describes a slowdown in the pace of aggregate labor productivity growth. We relate these patterns by studying changes in productivity growth from the late 1990s to the mid 2000s using firm-level data. We find that diminished allocative efficiency gains can account for the productivity slowdown in a manner that interacts with the within-firm productivity growth distribution. The evidence suggests that the decline in dynamism is reason for concern and sheds light on debates about the causes of slowing productivity growth.

Immigration and the Rise of American Ingenuity

in: American Economic Review, No. 5, 2017

Abstract

We build on the analysis in Akcigit, Grigsby, and Nicholas (2017) by using US patent and census data to examine the relationship between immigration and innovation. We construct a measure of foreign born expertise and show that technology areas where immigrant inventors were prevalent between 1880 and 1940 experienced more patenting and citations between 1940 and 2000. The contribution of immigrant inventors to US innovation was substantial. We also show that immigrant inventors were more productive than native born inventors; however, they received significantly lower levels of labor income. The immigrant inventor wage-gap cannot be explained by differentials in productivity.

Wage Bargaining Regimes and Firms' Adjustments to the Great Recession

in: ECB Working Paper, No. 2051, 2017

Abstract

The paper aims at investigating to what extent wage negotiation setups have shaped up firms’ response to the Great Recession, taking a firm-level cross-country perspective. We contribute to the literature by building a new micro-distributed database which merges data related to wage bargaining institutions (Wage Dynamic Network, WDN) with data on firm productivity and other relevant firm characteristics (CompNet). We use the database to study how firms reacted to the Great Recession in terms of variation in profits, wages, and employment. The paper shows that, in line with the theoretical predictions, centralized bargaining systems – as opposed to decentralized/firm level based ones – were accompanied by stronger downward wage rigidity, as well as cuts in employment and profits.