Productivity: More with Less by Better

Available resources are scarce. To sustain our society's income and living standards in a world with ecological and demographic change, we need to make smarter use of them.

Dossier

In a nutshell

Nobel Prize winners Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus state in their classic economics textbook: Economics matters because resources are scarce. Indeed, productivity research is at the very heart of economics as it describes the efficiency with which these scarce resources are transformed into goods and services and, hence, into social wealth. If the consumption of resources is to be reduced, e. g., due to ecological reasons, our society’s present material living standards can only be maintained by productivity growth. The aging of our society and the induced scarcity of labour is a major future challenge. Without productivity growth a solution is hard to imagine. To understand the processes triggering productivity growth, a look at micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments is indispensable.

Our experts

Department Head

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-708 Request per E-Mail

President

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-700 Request per E-MailAll experts, press releases, publications and events on “Productivity”

Productivity is output in relation to input. While the concept of total factor productivity describes how efficiently labour, machinery, and all combined inputs are used, labour productivity describes value added (Gross Domestic Product, GDP) per worker and measures, in a macroeconomic sense, income per worker.

Productivity Growth on the Slowdown

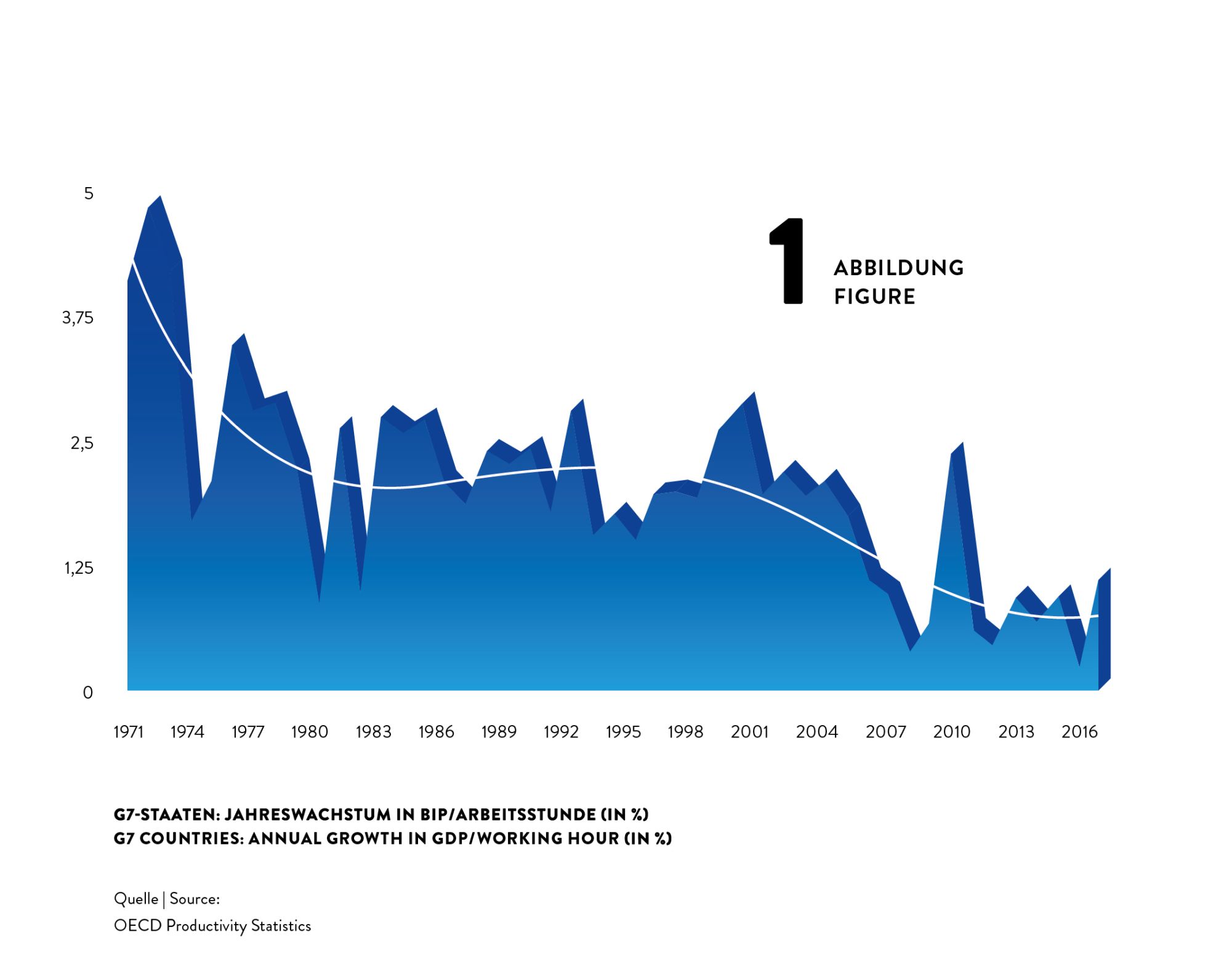

Surprisingly, despite of massive use of technology and rushing digitisation, advances in productivity have been slowing down during the last decades. Labour productivity growth used to be much higher in the 1960s and 1970s than it is now. For the G7 countries, for example, annual growth rates of GDP per hour worked declined from about 4% in the early 1970s to about 2% in the 1980s and 1990s and then even fell to about 1% after 2010 (see figure 1).

This implies a dramatic loss in potential income: Would the 4% productivity growth have been sustained over the four and a half decades from 1972 to 2017, G7 countries’ GDP per hour would now be unimaginable 2.5 times as high as it actually is. What a potential to, for instance, reduce poverty or to fund research on fundamentals topics as curing cancer or using fusion power!

So why has productivity growth declined dramatically although at the same time we see, for instance, a boom in new digital technologies that can be expected to increase productivity growth? For sure, part of the decline might be spurious and caused by mismeasurement of the contributions of digital technologies. For instance, it is inherently difficult to measure the value of a google search or another video on youtube. That being said, most observers agree that part of the slowdown is real.

Techno-Pessimists and Techno-Optimists

Techno-pessimists say, well, these new technologies are just not as consequential for productivity as, for instance, electrification or combustion engines have been. Techno-optimists argue that it can take many years until productivity effects of new technologies kick in, and it can come in multiple waves. New technology we have now may just be the tools to invent even more consequential innovations in the future.

While this strand of the discussion is concerned with the type of technology invented, others see the problem in that inventions nowadays may diffuse slowly from technological leaders to laggards creating a wedge between few superstar firms and the crowd (Akcigit et al., 2021). Increased market concentration and market power by superstar firms may reduce competitive pressure and the incentives to innovate.

Finally, reduced Schumpeterian business dynamism, i.e. a reduction in firm entry and exit as well as firm growth and decline, reflects a slowdown in the speed with which production factors are recombined to find their most productive match.

While the explanation for and the way out of the productivity puzzle are still unknown, it seems understood that using granular firm level data is the most promising path to find answers.

What are the Origins of Productivity Growth?

Aggregate productivity growth can originate from (i) a more efficient use of available inputs at the firm level as described above or (ii) from an improved allocation of resources between firms.

Higher efficiency at the firm level captures, e.g., the impact of innovations (Acemoglu et al., 2018) or improved firm organisation (management) (Heinz et al., 2020; Müller und Stegmaier, 2017), while improved factor allocation describes the degree of which scarce input factors are re-allocated from inefficient to efficient firms (‘Schumpeterian creative destruction’) (Aghion et al., 2015; Decker et al., 2021).

Most economic processes influence the productivity of existing firms and the growth and the use of resources of these firms and their competitors as well. The accelerated implementation of robotics in German plants (Deng et al., 2020), the foreign trade shocks induced by the rise of the Chinese economy (Bräuer et al., 2019), but also the COVID-19 pandemic, whose consequences are still to evaluate (Müller, 2021) not only effects on productivity and growth of the firms directly affected but at the same time may create new businesses and question existing firms.

While productivity can be measured at the level of aggregated sectors or economies, micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments are indispensable to study firm organisation, technology and innovation diffusion, superstar firms, market power, factor allocation and Schumpeterian business dynamism. The IWH adopts this micro approach within the EU Horizon 2020 project MICROPROD as well as with the CompNet research network.

As “creative destruction” may also negatively affect the persons involved (e. g., in the case of layoffs, Fackler et al., 2021), the IWH analyses the consequences of bankruptcies in its Bankruptcy Research Unit and looks at the implications of creative destruction for the society, e. g., within a project funded by Volkswagen Foundation searching for the economic origins of populism and in the framework of the Institute for Research on Social Cohesion.

Publications on “Productivity”

Aktuelle Trends: Entwicklung der Firmengründungen in Deutschland

in: Wirtschaft im Wandel, No. 1, 2020

Abstract

Das Produktivitätswachstum in entwickelten Volkswirtschaften hat sich in den letzten Jahren deutlich verlangsamt. Ein Indikator für die wirtschaftliche Dynamik in einer Volkswirtschaft ist die Firmengründungsaktivität. Wenn neue Ideen entstehen, kann dies in eine zunehmende Gründungsaktivität münden und so positiv auf die Produktivitätsentwicklung wirken.

Zu den betrieblichen Effekten der Investitionsförderung im Rahmen der deutschen Regionalpolitik

in: Wirtschaft im Wandel, No. 1, 2020

Abstract

Die Wirtschaft in den Industrieländern unterliegt einem ständigen Anpassungsdruck. Wichtige aktuelle Treiber des Strukturwandels sind vor allem die Globalisierung, der technologische Fortschritt (insbesondere durch Digitalisierung und Automatisierung), die Demographie (durch Alterung und Schrumpfung der Bevölkerung) und der Klimawandel. Von diesem Anpassungsdruck sind jedoch die Regionen in Deutschland sehr unterschiedlich betroffen. Regionalpolitik verfolgt das Ziel, Regionen bei der Bewältigung des Strukturwandels zu unterstützen. Ein besonderer Fokus liegt dabei auf Regionen, die ohnehin durch Strukturschwächen gekennzeichnet sind. Die aktuelle Regionalförderung in Deutschland basiert im Wesentlichen auf der Förderung von Investitionen von Betrieben und Kommunen. Die Evaluierung dieser Programme muss integraler Bestandteil der Regionalpolitik sein – schließlich stellt sich immer die Frage nach einer alternativen Verwendung knapper öffentlicher Mittel. Eine Pilotstudie für Sachsen-Anhalt zeigt, dass die im Rahmen der Regionalpolitik gewährten Investitionszuschüsse einen positiven Effekt auf Beschäftigung und Investitionen der geförderten Betriebe haben; bei den Investitionen allerdings nur für die Dauer des Projekts. Effekte der Förderung auf Umsatz und Produktivität von Betrieben in Sachsen-Anhalt waren nicht nachweisbar.

Connecting to Power: Political Connections, Innovation, and Firm Dynamics

in: NBER Working Paper, No. 25136, 2018

Abstract

How do political connections affect firm dynamics, innovation, and creative destruction? To answer this question, we build a firm dynamics model, where we allow firms to invest in innovation and/or political connection to advance their productivity and to overcome certain market frictions. Our model generates a number of theoretical testable predictions and highlights a new interaction between static gains and dynamic losses from rent-seeking in aggregate productivity. We test the predictions of our model using a brand-new dataset on Italian firms and their workers, spanning the period from 1993 to 2014, where we merge: (i) firm-level balance sheet data; (ii) social security data on the universe of workers; (iii) patent data from the European Patent Office; (iv) the national registry of local politicians; and (v) detailed data on local elections in Italy. We find that firm-level political connections are widespread, especially among large firms, and that industries with a larger share of politically connected firms feature worse firm dynamics. We identify a leadership paradox: when compared to their competitors, market leaders are much more likely to be politically connected, but much less likely to innovate. In addition, political connections relate to a higher rate of survival, as well as growth in employment and revenue, but not in productivity – a result that we also confirm using a regression discontinuity design.

Intangible Capital and Productivity. Firm-level Evidence from German Manufacturing

in: IWH Discussion Papers, No. 1, 2020

Abstract

We study the importance of intangible capital (R&D, software, patents) for the measurement of productivity using firm-level panel data from German manufacturing. We first document a number of facts on the evolution of intangible investment over time, and its distribution across firms. Aggregate intangible investment increased over time. However, the distribution of intangible investment, even more so than that of physical investment, is heavily right-skewed, with many firms investing nothing or little, and a few firms having very large intensities. Intangible investment is also lumpy. Firms that invest more intensively in intangibles (per capita or as sales share) also tend to be more productive. In a second step, we estimate production functions with and without intangible capital using recent control function approaches to account for the simultaneity of input choice and unobserved productivity shocks. We find a positive output elasticity for research and development (R&D) and, to a lesser extent, software and patent investment. Moreover, the production function estimates show substantial heterogeneity in the output elasticities across industries and firms. While intangible capital has small effects for firms with low intangible intensity, there are strong positive effects for high-intensity firms. Finally, including intangibles in a gross output production function reduces productivity dispersion (measured by the 90-10 decile range) on average by 3%, in some industries as much as nearly 9%.

Labor Market Power and the Distorting Effects of International Trade

in: International Journal of Industrial Organization, January 2020

Abstract

This article examines how final product trade with China shapes and interacts with labor market imperfections that create market power in labor markets and prevent an efficient market outcome. I develop a framework for measuring such labor market power distortions in monetary terms and document large degrees of these distortions in Germany's manufacturing sector. Import competition only exerts labor market disciplining effects if firms, rather than employees, possess labor market power. Otherwise, increasing export demand and import competition both fortify existing distortions, which decreases labor market efficiency. This widens the gap between potential and realized output and thus diminishes classical gains from trade.